- Home

- Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Page 8

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Read online

Page 8

It was a long two minutes while we waited for our scores. We were in the “kiss and cry” area with Louis and Sandra, jumping up and down. Everyone was screaming. We kept looking up to Johnny Esaw—he always had the results first on his monitor—but he was so excited that he pulled the cord out of his computer by accident, and the screen went blank! Everyone was wondering: Did we do it? Did we do it? I think we all knew in our hearts that we had, but it wasn’t until we saw and heard the string of 5.8s and 5.9s that we really believed it.

Our dream had come true: we were the new world champions! It was so amazing to realize that we had gone from the lowest possible low to the highest possible high in just three weeks. We had defeated the Russian team that had taken the Olympic gold only three weeks earlier, and the East Germans who had been world champions two years previously.

We stood on the podium with two sets of world champions and the Olympic champions. The flags began to go up. We waited, hearts beating, for the Canadian flag to rise to the top of the pole—but it became caught on something and was lowered again! I thought, No, no, no. This is such an amazing moment. Don’t ruin it. But they unhooked the flag, sent it back up and then the sounds of “O Canada” spread across the arena. As we stood there listening to our national anthem, it felt like we had ten thousand friends sharing this special moment with us. After all we had been through, it seemed like a miracle that we had managed to deliver two perfect programs. We both had tears running down our faces. It was amazing going from what we were feeling a week earlier to being part of this incredible celebration! To this day, every time I see a Canadian flag go up, I relive that moment at the World Championships.

All these years later, people will stop one of us in a mall or on the street—they recognize us—and say, “I was there that day. . . . I was there.” And we instantly know that they mean they were there in Ottawa, when we skated that miraculous, memorable skate.

Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini

Mississauga and Bradford, Ontario

To The Top Canada!

I have one love—Canada; One purpose— Canada’s greatness; One aim—Canadian unity from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Former Prime Minister John G. Diefenbacker

I could not sleep. I quietly stared at the ceiling. Ten hours left before the media conference that would begin the To The Top Canada! expedition. Like a racehorse in the starting gate, I was ready to go. I knew I was about to start the most challenging year of my life.

A short time later, in the cold morning air, I pushed my heavily loaded mountain bike from the beach up to the road. Accompanied by an army of local cyclists, I pulled out of Point Pelee. It was March 1, 1997, and the To The Top Canada! expedition had begun! A large contingent of media was there to see me off, and I pulled out the big Canadian flag that I’d bought for the Montreal Rally back in 1995. People cheered and waved as I went by, and cars honked their horns. As they followed my progress across Canada, the media quickly dubbed me “The Unity Guy.”

The emotional rally in Montreal before the Québec Referendum in October 1995 had changed my life. My eleven-year-old son, James, was at my side. Like so many Canadians, we were filled with anxiety about the referendum’s outcome. That day, tens of thousands of Canadians made a difference by coming to Montreal and standing tall for Canada. I knew then that I had do something myself. Something personal, something to help make Canada a better country.

And so it was that the To The Top Canada! expedition was born. By cycling, alone, the 6,520 kilometres from Point Pelee to Tuktoyaktuk, I’d be the first person in history to travel from the bottom of Canada to the very top—under his own power. The second and more important goal of the expedition was to get Canadians’ attention and ask them one question: “What will you do to make Canada a better country than when you found it?” The expedition wasn’t so much about being the first to travel to the top of Canada, as it was a dream to take Canada to the top of its potential.

As a professional speaker I’d travelled to many countries, and I knew Canada was the best of them all. I knew the greatest legacy I could leave my son was a strong, united Canada. Even at his age, he realized the growing pains we faced as a nation. That rally in Montreal changed his life, too, and when I announced I was leaving home for almost a year to fight for Canada, he understood. My wife, Carol, also understood my passion, and as a family we decided to cash in our life savings to allow the To The Top Canada! expedition to go forward. I believed if thirty million Canadians each did one personal project to make Canada better, the result would be a synergy that would empower our country and exceed everyone’s expectations.

I didn’t look like a cyclist; at 272 pounds I looked more like a retired linebacker for the Hamilton Ti-Cats. And at age forty-one I was about to start a near-impossible journey. Roads in Canada go only as far north as Inuvik in Canada’s Arctic, and then they stop. Once in Inuvik, I would have to wait for the middle of the Arctic winter when the mighty Mackenzie River froze. Then, in total darkness and temperatures of -50°C, I would ride my mountain bike on an ice trail down the centre of the river, then out onto the Arctic Ocean to reach Tuktoyaktuk. Many cynics and critics thought I could never pull it off, but I was determined to prove them wrong.

As the days passed, and I rode in and out of communities, people would recognize “the unity guy” they had seen on TV. The month of May found me along the shores of Lake Superior, and by early June, I was approaching Thunder Bay. As I passed the Terry Fox Memorial, I remembered the emotional day when I’d seen Canada’s greatest hero sprint to Toronto City Hall, and it inspired me on. After that, when things got very rough and discouragement set in, I’d think of Terry—he never gave up, and neither would I.

On July 1, I reached Yorkton, Saskatchewan, did a radio interview and participated in Canada Day celebrations. The local high school band played “O Canada,” and I spoke passionately to the crowd about my love for Canada. They came alive when I had them cheer, “I Am Canadian!”

After the blistering hot days of the prairie summer, I rode through the Rockies and into the beautiful fall days of British Columbia. After that I faced weather that got progressively colder. On September 17, I rode into Dawson City, Yukon. It was eighty-two kilometres off my route, but its history seemed too important to miss. The city still had the spirit of the Klondike—all the buildings, the dirt roads and the wooden walkways looked like they were fresh from 1898.

I had now cycled over 6,000 kilometres. The gears on my mountain bike were stripped, and I was exhausted after fighting hundreds of kilometres of mountains and mud on the dirt trail called the Dempster Highway. I was tired, wet, hungry and cold, and very glad to arrive in Fort McPherson, a Gwich’in First Nation community just north of the Arctic Circle. So far I’d spoken from my heart in forty-seven cities, to over five million Canadians. Now, during a radio interview with Bertha Francis, radio host for Gwich’in station CBQM, I spoke enthusiastically about the U.N. Report that had ranked Canada “number one”—the best country in the world in terms of education, health care and income—not just once, but three years in a row!

That’s when Bertha jumped in with excitement and exclaimed: “Canada is the best country in the world, and we should all be thankful we have been blessed with an abundance of caribou and berries!”

It took a moment, but then the significance of her words struck me like a bolt of lightning. For people who lived off the land, caribou and berries meant the difference between life and death. Bertha hadn’t said to be thankful for nice clothes, or a new car, or a big house. What she had really said was to be thankful you are alive, and living in this great country!

On September 29, I awoke to a heavy blanket of snow, and once back on the road, the mud was even worse than before. With all my dry winter clothes gone and almost no food left, I decided to ride straight on to Inuvik, still 112 kilometres away. Around 8:00 P.M., hungry and thirsty, I met a family who called out, “You’ve made it! You’ve made it to the top

!” And the whole family clapped and cheered from their truck.

Now I had to rest my expedition until the Mackenzie River froze. Finally, on January 5, in the midst of the total darkness of the Arctic winter, I began the last leg of my journey. With special protective clothing, goggles and a face mask, I battled Arctic winds and ploughed through snow in temperatures colder than -50°C. I was startled to discover that rather than hugging the coast, the ice trail actually went five to ten kilometres out into the Arctic Ocean. There were cracks in the ice with seawater gushing out, and as I rode on alone, the cracking sounds made me shiver. Even so, I marvelled at the incredible beauty of the northern lights as they glowed fluorescent green and looked like shimmering curtains that danced in the sky. I was exhilarated and thankful to be alive.

On Wednesday January 7, 1998, I proudly carried my Canadian flag over the last few metres, and was welcomed by a mass of media and community elders when I arrived at a school in Tuktoyaktuk. It was packed with young and old, and as I wheeled my bike into the gym, they made a tunnel for me through the crowd. It was lined with Tuktoyaktuk drummers, and everyone was clapping and cheering. A giant multicoloured “CONGRATULATIONS!” sign ran the length of the gym. Tears came to my eyes from the warmth that poured from the entire community. After the formalities, the mayor of “Tuk” introduced the drummers, and then the dancers performed in my honour.

As I left the gym, a crowd surrounded me—people shook my hand and patted my back. It was a moment that money could never buy. I let the feeling sink in, knowing I’d treasure the memory for the rest of my life. Later I called my wife; she had already heard me on the CBC, and friends were calling to say they had as well. I was thrilled to know my Canadian unity message was spreading across Canada like wildfire. I’m proud to say my journey was a success—it sent a message to all Canadians that any dream is possible to make Canada the best country in the world during the twenty-first century!

Chris Robertson

Hamilton, Ontario

©1997 John Cadiz. From Lost in the Wilds of Canada by John Cadiz. Used by permission, McClelland & Stewart Ltd. The Canadian publishers.

Our Olympic Dream

People talk about world peace, and I wish that there was some way to extend the experiences of international athletes to everyone. Thus enlightened, we would have a much better chance at achieving that world peace.

Brian Orser

It didn’t start out as an Olympic dream. Back in elementary school in Montreal, we were a pair of overweight, uncoordinated twins. During gym class, when teams were chosen, it didn’t matter if the game was baseball, dodge ball or lacrosse, we were always last to be picked.

It was so bad, our teacher said to us one day, “Penny and Vicky, you have been chosen, along with four other kids, to miss music class and go to remedial gym.” This was because neither one of us could catch or throw a ball. We were totally mortified.

Although this humiliation whittled away at our self-esteem, we continued to try other sports and activities outside of school. Then, at age eight, we discovered synchronized swimming. It was as if the sport had chosen us, since it was the only one we were good at, and we loved it.

It was an ideal sport for identical twins, and we had great fun creating routines to music. We passionately loved working with other swimmers and our coaches and practiced incredibly hard. Each year we set higher goals and became more successful. Then, in 1979, at the age of fifteen, we were thrilled to represent Québec at the Canada Games. Subsequent victories allowed us to travel all over the world, and our dream to participate in the Olympics was born.

We achieved many of our goals, including being seven-time Canadian synchronized swimming duet champions, and World champions in Team. We were thrilled to be the first duet in the world to ever receive a perfect mark of “10”.

But to our great disappointment, the 1980 Olympic Games eluded us when they were boycotted by many countries, including Canada. Then, in 1984, we didn’t make the team. After fourteen years of training and striving, we had to accept that our Olympic dream would remain out of reach. We retired from swimming to finish our degrees at McGill and start our careers.

Then, one day five years later, while watching a synchro competition, we both experienced an unexpected sensation. We suddenly realized our Olympic dream was still alive, and we could no longer ignore it. On April Fool’s Day, 1990, we decided to make an unprecedented comeback and shoot for the 1992 Olympics. We were afraid to announce our plans in case we didn’t make it, but in the end, we were more afraid of not trying and having to live with the thought of “What if?” We decided to give it our all, and take pride in simply doing our best. “Si on n’essaie pas, on ne le saura jamais!” we said—“If we don’t try, we’ll never know!”

Everyone said it would be impossible. But our intense desire provided the energy needed to persevere. We only had two years to get back in shape and be among the best in the world. No swimmer had ever come back after a five-year absence, especially not at the age of twenty-seven!

We weren’t eligible for any funding, so we both maintained full-time jobs and trained five hours every day after work. We still had to support ourselves and fund all our travel to international competitions. We were determined to succeed, vowing, “Nothing will stop us this time.” For two full years we maintained that gruelling schedule without ever knowing if we’d make it.

Thankfully, we had four dedicated coaches from Québec who poured their hearts and souls into helping us achieve our dream. Julie was our head coach, André directed our weight training, Richard helped us improve our conditioning and Denise helped with our accuracy in the water. We never could have done it without them.

We were pushed to our physical limits during training since we had to make up for the five years off. Through it all, however, we still loved it and maintained our sense of humour. Sometimes we laughed so hard with Julie we ran out of air and ended up sinking to the bottom of the pool. Julie helped us to continue believing in ourselves. We can still hear her saying: “Okay les jumelles, vous êtes capables!” — “Okay, twins, you can do this!”

The day of the Olympic trials finally came. We were confident but nervous. We could hardly breathe as we waited to hear our marks in finals. When they were announced, we jumped up and down hugging each other—we had won by 0.04! In that incredible moment we realized we were finally going to live our Olympic dream!

We could hardly contain our excitement as Canada’s ’92 Olympic team gathered in Toronto, en route to Barcelona. When we received our Olympic outfits, we felt just like kids at Christmas! Then Ken Read, our chef de mission, called a meeting and said to the group: “Congratulations and welcome to the Canadian Olympic Team! You are now Olympians and no one will ever take that away from you.”

Our Olympic experience was unforgettable. During the opening ceremonies, we were thrilled to walk into the packed stadium to thunderous applause, with hundreds of Canadian flags being waved. We also found out how much support we had from Canadians everywhere. Thanks to the Olympic Mailbag Program organized by Canada Post, our spirits received a tremendous lift during those last few stressful days of training. Many Canadians wrote their thoughts and wishes on a postcard simply addressed to “Penny and Vicky Vilagos—Barcelona.” After practice each day, we rushed to dig through the giant pile of bright yellow postcards sent to the Canadian team, and pick out those addressed to us. They came in French and in English, from old childhood friends in Montreal and Québec, complete strangers, former athletes, and proud Canadians young and old. They inspired us, made us laugh and even made us cry. Imagine how we felt when we read this incredible message:

Dear Penny and Vicky: You are swimming my dream. I used to be able to swim two lengths of the pool in a single breath. I am now disabled and can no longer swim at all. I am sending you my strength—May the sun shine on you.

And the sun did shine on us in Barcelona.

Finally, our big day came. We felt considerable stress kn

owing millions of viewers would be watching, but we were ready. As we stepped onto the pool deck and heard, “Competitor #9 . . . Canada!” we almost burst with pride. As the Canadians cheered and waved their flags, we looked at the water to focus on the job at hand. The temptation in the moment was to reflect on the 30,000 hours of training it had taken to get here, but there would be time for that later. . . .

Swimming for Canada that day was magical. Despite the stress, we enjoyed every moment. As the music ended and the applause began, we looked up at Julie, and her expression told us what we already felt—we had given the performance of our lives!

Finally, wearing our Canada tracksuits, we marched around the pool for the medal ceremony. As we stepped on the podium to receive our silver medals, in our minds our coaches were there with us to share this special moment. As we watched the flag go up, the awareness that so many Canadians were proud of us made it that much better.

Still floating on a cloud, it was soon time for the closing ceremonies. We’ll remember forever the electric atmosphere in the stadium as everyone swayed back and forth and joined in singing “Amigos Para Siempre,” or “Friends for Life”. And then it began to sink in—after twenty-one years, our Olympic dream had finally come true!

Penny and Vicky Vilagos

Montreal, Québec

3

OVERCOMING

OBSTACLES

The greater the difficulty, the more glory in surmounting it.

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Chicken Soup for the Soul of America

Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul

Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues

Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul

Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers

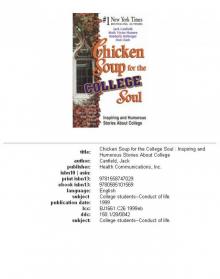

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Chicken Soup for the College Soul

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference

Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter

Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories

Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul Chicken Soup for the African American Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Soul 101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13

101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13 Christmas Magic

Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs Chicken Soup for the Country Soul

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul)

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul) A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul The Book of Christmas Virtues

The Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Little Souls

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II