- Home

- Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Page 8

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Read online

Page 8

"And he also seems to have a lot of rage," says Little Freud, plunging on. "His id has taken over, and his superego has collapsed. He seems to be entertaining some classic primordial fixations. In fact, I think he wants to kill me."

"He doesn't really want to kill you, dear," says Simple Mind. "I've hired him to do it for me."

"Classic projection," says Little Freud, disgustedly.

Beth Mullally

Page 67

3

LESSONS FROM THE CLASSROOM

The illiterate of the future will not be the person who cannot read. It will be the person who does not know how to learn.

Alvin Toffler

Page 68

Undeclared

It echoed through the hallways and out onto the quad like some ancient Gregorian chant. Everyone was asking it. It was the new catchphrase. It was the new pickup linemore popular than "What's your sign?" But I had no answer. I dreaded the question. I was undeclared, like some contraband being smuggled across an international border. Like an astronaut floating untethered through space, I had no purpose in life. I would rather have taken the SAT again than have to face the question, "What's your major?"

And tomorrow was the last day to declare a major. The last day! Everyone else was happily moving forward in their lives, striving toward careers in anthropology, sociology, molecular biology and the like. "Don't worry," my friends would say. "You can always major in business." Business? Not me. I was an artist. I would rather have died than majored in business. In fact, I didn't even need college. I could just go out into the world, and my great talents would be immediately recognized.

On the night before my fate was to be declared, my parents were having a dinner party for some of their friends. Sanctuary! What would my parents' friends care about majors? I could eat dinner in peace and take a break from

Page 69

my inner angst for a couple of hours.

I was wrong. All they could talk about was majors. They each had to share their majors with me, and each had an opinion as to what mine should be. All their advice didn't put me any closer to a major. It just confused me even more. None of our dinner guests seemed particularly suited for their chosen professions. Dr. Elkins, the dentist, had spinach in his teeth. Mrs. Jenkins, the industrial chemist, put ketchup on her veal. And Mr. Albertson, the hydro-engineer, kept knocking over his water glass.

Dinner was over, everyone left, the night was getting later, and yet I was still undeclared. I got out the catalog and began paging through the possibilities for the millionth time. Aeronautical engineering? I get airsickness. Chinese? I'd always wanted to go to China, but it seemed I could go there without majoring in it. Dentistry? Just then I happened to look in the mirror and notice spinach in my teeth. This was hopeless.

As college students are prone to do, I decided that if I just slept for a while and woke up really early, I would be able to manifest a major. I don't know exactly what it is in the college student's brain that thinks some magical process occurs between 2:00 A.M. and 6:00 A.M. that will suddenly make everything more clear.

It had worked for me in the past, but not this time. In fact, as college students are also prone to do, I overslept. I woke up at 10:00 A.M. I had missed my first class, Physics for Poets, and I had three hours to commit the rest of my life to something, anything. There was always business.

I left for campus hoping for a divine major-declaring inspiration between my house and the administration building that would point me in the right direction. Maybe a stranger would pass by on the street and say, "This is what you should do for the rest of your life: animal husbandry." Maybe I would see someone hard at

Page 70

work and become inspired to pursue the same career. I did see a troupe of Hare Krishnas who didn't seem particularly troubled about majors, but that didn't quite seem to be a career path suited to my temperament. I passed a movie theater playing Once Is Not Enough, and was tempted to duck inside and enjoy the film based on Jacqueline Susann's bestselling novel and starring David Janssen. I passed up the temptation. But, wait a minute! Movies. I love movies! I could major in movies. No, there is no major in movies. Film, you idiot, I thought. That's it! I was lost but now I was found. I was declared.

Fifteen years later, I think of all my friends who so confidently began college with their majors declared. Of those who went around snottily asking, "What's your major?" very few are working in their chosen professions. I didn't end up a filmmaker. In fact, I'm now on my fourth careerand some days, I still feel undeclared. It really doesn't matter what you major in, as long as you get the most out of college. Study what interests you, and enjoy learning about the world. There is plenty of time to decide what you will do with the rest of your life.

Tal Vigderson

Page 71

Making the Grade

In 1951, I was eighteen and traveling with all the money I had in the worldfifty dollars. I was on a bus heading from Los Angeles to Berkeley. My dream of attending the university was coming true. I'd already paid tuition for the semester and for one month at the co-op residence. After that, I had to furnish the restmy impoverished parents couldn't rescue me.

I'd been on my own as a live-in mother's helper since I was fifteen, leaving high school at noon to care for children till midnight. All through high school and my first year of college, I'd longed to participate in extracurricular activities, but my job made that impossible. Now that I was transferring to Berkeley, I hoped to earn a scholarship.

That first week I found a waitress job, baby-sat and washed dishes at the co-op as part of my rent. At the end of the semester, I had the B average I needed for a scholarship. All I had to do was achieve the B average next term.

It didn't occur to me to take a snap course; I'd come to the university to learn something. I believed I could excel academically and take tough subjects.

One such course was a survey of world literature. It was taught by Professor Sears Jayne, who roamed the

Page 72

stage of a huge auditorium, wearing a microphone while lecturing to packed rows. There was no text. Instead, we used paperbacks. Budgetwise, this made it easier since I could buy them as needed.

I was fascinated with the concepts he presented. To many students, it was just a degree requirement, but to me it was a feast of exciting ideas. My co-op friends who were also taking the course asked for my help. We formed a study group, which I led.

When I took the first examall essay questionsI was sure I'd done well. On the ground floor, amid tables heaped with test booklets, I picked out mine. There in red was my grade, a 77, C-plus. I was shocked. English was my best subject! To add insult to injury, I found that my study-mates had received Bs. They thanked me for my coaching.

I confronted the teaching assistant, who referred me to Professor Jayne, who listened to my impassioned arguments but remained unmoved.

I'd never questioned a teacher about a grade beforenever had to. It didn't occur to me to plead my need for a scholarship; I wanted justice, not pity. I was convinced that my answers merited a higher grade.

I resolved to try harder, although I didn't know what that meant because school had always been easy for me. I'd used persistence in finding jobs or scrubbing floors, but not in pushing myself intellectually. Although I chose challenging courses, I was used to coasting toward As.

I read the paperbacks more carefully, but my efforts yielded another 77. Again, C-plus for me and Bs and As for my pals, who thanked me profusely. Again, I returned to Dr. Jayne and questioned his judgment irreverently. Again, he listened patiently, discussed the material with me, but wouldn't budgethe C-plus stood. He seemed fascinated by my ardor in discussing the course ideas, but my dreams of a scholarship and extracurricular activities were fading fast.

Page 73

One more test before the final. One more chance to redeem myself. Yet another hurdle loomed. The last book we studied, T. S. Eliot's The Wasteland, was available only in hardb

ack. Too expensive for my budget.

I borrowed it from the library. However, I knew I needed my own book to annotate. I couldn't afford a big library fine either. In 1951, there were no copying machines, so it seemed logical to haul out my trusty old Royal manual typewriter and start copying all 420 pages. In between waitressing, washing dishes, attending classes, baby-sitting, and tutoring the study group, I managed to pound them out.

I redoubled my efforts for this third exam. For the first time, I learned the meaning of the word "thorough." I'd never realized how hard other students struggled for what came easily to me.

My efforts did absolutely no good. Everything, down to the dreaded 77, went as before. Back I marched into Dr. Jayne's office. I dragged out my dog-eared, note-blackened texts, arguing my points as I had done before. When I came to the sheaf of papers that were my typed copy of The Wasteland, he asked, "What's this?"

"I had no money left to buy it, so I copied it." I didn't think this unusual. Improvising was routine for me.

Something changed in Dr. Jayne's usually jovial face. He was quiet for a long time. Then we returned to our regular lively debate on what these writers truly meant. When I left, I still had my third 77definitely not a lucky number for meand the humiliation of being a seminar leader, trailing far behind my ever-grateful students.

The last hurdle was the final. No matter what grade I got, it wouldn't cancel three C-pluses. I might as well kiss the scholarship good-bye. Besides, what was the use? I could cram till my eyes teared, and the result would be a crushing 77.

Page 74

I skipped studying. I felt I knew the material as well as I ever would. Hadn't I reread the books many times and explained them to my buddies? Wasn't The Wasteland resounding in my brain? The night before the final, I treated myself to a movie.

I sauntered into the auditorium and decided that for once I'd have fun with a test. I marooned all the writers we'd studied on an island and wrote a debate in which they argued their positions. It was silly, befitting my nothing-to-lose mood. The words flowedall that sparring with Dr. Jayne made it effortless.

A week later, I strolled down to the ground floor (ground zero for me) and unearthed my test from the heaps of exams. There, in red ink on the blue cover, was an A. I couldn't believe my eyes.

I hurried to Dr. Jayne's office. He seemed to be expecting me, although I didn't have an appointment. I launched into righteous indignation. How come I received a C-plus every time I slaved and now, when I'd written a spoof, I earned an A?

''I knew that if I gave you the As you deserved, you wouldn't continue to work as hard.''

I stared at him, realizing that his analysis and strategy were correct. I had worked my head off, as I had never done before.

He rose and pulled a book from his crowded shelves. "This is for you."

It was a hardback copy of The Wasteland. On the flyleaf was an inscription to me. For once in my talkative life, I was speechless.

I was speechless again when my course grade arrived: A-plus. I believe it was the only A-plus given.

Next year, when I received my scholarship:

I cowrote, acted, sang and danced in an original musical comedy produced by the Associated Students. It played in

Page 75

the largest auditorium to standing-room-only houses.

I reviewed theater for the Daily Cal, the student campus newspaper.

I wrote a one-act play, among the first to debut at the new campus theater.

I acted in plays produced by the drama department.

The creative spark that had been buried under dishes, diapers and drudgery now flamed into life. I don't recall much of what I learned in those courses of long ago, but I'll never forget the fun I had writing and acting.

And I've always remembered Dr. Jayne's lesson. Know that you have untapped powers within you. That you must use them, even if you can get by without trying. That you alone must set your own standard of excellence.

Varda One

Page 76

The Good, the Bad and the Emmy

"And the winner is . . ."

What a thrill to rush onstage to receive my Emmy for "Best Children's Program." The applause. The cheers. All the long hours and hard work put into writing and producing Jim Henson's Muppet Babies had paid off in a big way.

A lofty time like this is even more thrilling when compared to your low times. Times when you're certain a high like this isn't even possible. I'm talking crash, boom, thud times! Like that bottom-of-the-barrel time I had back in college . . .

Long before I was an Emmy winner, I was a drama student at San Diego State University. Every senior in the department is required to direct and produce a one-act play. It's a senior's biggest projectthe crowning achievement of his or her college career. I was eager for my turn, determined to write and direct my own play. After all, if Woody Allen could write and direct his own material, so could I.

The drama department, however, felt differently. They had a strict rule that no student could direct a one-act play that he or she had written. It was a rule I disagreed with then and still disagree with today. Despite my arguments,

Page 77

the department heads wouldn't budge. So, clever lad that I am, I submitted a one-act play I had written under a pseudonym, George Spelvin. My clever plan worked.

My play, I mean George's play, The Life of the Party, was a farce. I chose my cast carefully, and we had a ball rehearsing. We were positive we had a collegiate hit on our hands. Eventually, our play was ready for its technical dress rehearsal.

The "tech-dress" took place the day before the performance and was the only opportunity the director and cast had to add sound effects, lighting, props and costumesfeats all performed by student technicians. It was the techies' first exposure to the play and my cast's first exposure to an audience, albeit a small one.

We launched into our tech-dress rehearsal with excitement and enthusiasm, and the techies performed their jobs admirably. My actors, on the other hand, were having a tough time. Somehow, with the addition of costumes and a set and under hot lights, this farce didn't play very funny. It creaked and groaned. My actors expected to hear laughs from the techies, but the laughs never came. Were the techies too busy? Didn't they have a sense of humor? My actors' confidence was shaken, and so was mine.

Afterward the head technician approached me and said, "You know the old saying: A bad dress rehearsal makes for a great opening!" I tried to smile back. This wasn't just a bad rehearsal; it felt like a ride on the Hindenburg. I put on my bravest face for my cast, gave a few notes and assured them they'd be terrific for the next day's performance. Tired, weary and skeptical, my actors retreated to their dorms.

The next day, the most anticipated day of my college career, I watched as the theater filled with students and faculty. I crossed my fingers as the lights went down and the music came up. To put the audience in the mood for a

Page 78

farce, I chose Carl Stalling's musical theme from The Bugs Bunny Show. Just hearing the music, the audience roared with laughter. I relaxed and uncrossed my fingers. What was there to worry about?

Plenty! My actors made their entrances, and, in the beginning, there was a smattering of laughter. The audience was rooting for them. They wanted to be entertained. As the show progressed, however, the laughs became fewer and fewer . . . before they disappeared altogether. Soon, my actors were sweatingand it wasn't because of the hot lights. There were long stretches of inappropriate silence. Nothing was working. The play was dreadful, too painful to watch. I watched the audience instead. Watched them glance at their watches, watched them cough, roll their eyes. The second the play was over, they bolted for the nearest exit. Yes, it stank, but they behaved as if they actually required fresh air.

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul

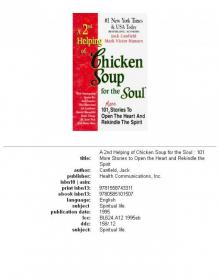

Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Chicken Soup for the Soul of America

Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul

Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues

Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul

Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Chicken Soup for the College Soul

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference

Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter

Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories

Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul Chicken Soup for the African American Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Soul 101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13

101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13 Christmas Magic

Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs Chicken Soup for the Country Soul

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul)

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul) A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul The Book of Christmas Virtues

The Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Little Souls

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II