- Home

- Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Page 5

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Read online

Page 5

When I had earned enough to afford rent someplace, I couldn't find any apartments that would accept four children, so we checked into a hotel. It was like being on a fantastic furlough. We were thrilled, reveling in the heat, the beds, the safety. We sneaked in our rations to cook and learned to prepare savory meals with a two-burner hot plate. We cooled dairy items in the bathtub. (Hotels have lots of ice.)

Finally, many months later, the landlord of the promised house sent me a money order refunding all that

Page 25

was due me, with many apologies. I used the money to find us an apartment.

That was thirteen years ago. I'm sharing command now with a husband, and we keep our children in a wonderfully large house. Every morning, when I run the inspection on my troopstaller now, looking at me eye to eyeI think back on the horrible enemy of desperation that we fought and defeated together. And then I thank God for my small soldiers: a courageous, tough little crew who never stumbled in their frightening march. Their bravery was the stuff of the greatest of heroes.

Rachel Berry

Page 26

Page 27

Journey Out of Silence

Nothing can stop the man with the right mental attitude from achieving his goal; and nothing on earth can help the man with the wrong mental attitude.

Thomas Jefferson

My adventure began in October 1966, when Miss Neff, my occupational therapist, took me into her stale, windowless room. She was a thirty-year-old woman barely above five feet tall, but she could make a student who was labeled as uncooperative at the Dr. J. P. Lord School for the Physically Handicapped tremble in his wheelchair with fear. As one of them, I was scared to death when she came to get me for an unscheduled visit.

Then, I was labeled a horrible little boy who wouldn't do what his therapist told him to do. I seemed rebellious because I was so uncoordinated: Even after years of physical, speech and occupational therapy, I still could not walk, talk or use my hands.

Sometimes I asked myself, Why should I make the effort? As Miss Neff told my parents, ''We always try to do what

Page 28

we've done in other, similar situations, and if that doesn't work, we look for something new." But nothingold or newwas working for me.

There I was, at any rate, being pushed by Miss Neff into her office when it wasn't even time for my therapy. I was petrified! What had I done wrong this time? Had they finally given up on me? Was I getting kicked out of school? I felt like Daniel wheeling into a stuffy lions' den.

Miss Neff parked me in front of her steel teacher's desk, then she sat in her armless chair behind it. Instead of scolding me, as I had anticipated, she showed me some mimeographed diagrams of what looked like a large but poorly shaped slingshot that was rounded at the fork. It looked ridiculous to me. Then she showed me another diagram of a kid typing with this contraption on his head.

During that year's teachers' convention, Miss Neffalong with the school's speech therapist, physical therapist and Mrs. Clanton, my new classroom teacherattended another special school that was in Iowa City. At that school, they saw a student using a headstick to type his schoolwork.

"This is a headstick," she said sternly. "It is not a toy or a weapon. We think that you will be able to use it if you want to, but it will be very hard work. And if I ever see you using it to poke somebody, I'll take it away from you and set it on this desk. Understand?"

I nodded stiffly.

"Now," she continued, "at the next PTA meeting, I will give your mother some directions for exercises to strengthen your neck. I suggest that you do them at home every day. I also suggest that you do them in the morning when you are fresh. It will be tiresome work, but you just might be able to do it."

After Miss Neff lectured me, Mrs. Clanton who, unlike all my therapists, had not witnessed my many failures

Page 29

said simply, "I think you can do it. Do you?"

I nodded. My journey from solitary confinement had begun. Every day I did my neck exercises before going to school. After a family friend crafted me a homemade headstick to use, I practiced using it at school to turn the pages of a spiral-bound book; to point to words on an elaborate language board made by my speech therapist, and, of course, to do those lovely neck exercises. I cannot give you a day-by-day description of my first real taste of success. It was like a dream. Up until this adventure with the headstick, everything the therapist had tried on me had not worked because I was so uncoordinated that I gave up in frustration. But this was different.

Mrs. Clanton believed in me. If she'd said I could fly, I would have jumped off the Empire State Building without any reservations and flapped my spindly arms until I splattered on the sidewalk. She was a friend as well as a teacher. I still remember how she played baseball with my class to make up for an extremely dull recreation hour when we had to sit through an inaudible play. So I worked hard to please her, not minding the very few disappointments of this project.

My teacher and therapists thought that I was intelligent because they watched my eyes and facial expressions during my lessons. But as Mrs. Clanton told my parents, "We have no way of testing his knowledge of each of his subjects."

The climax of this successful adventure came when Miss Neff put me in a straight-backed wooden chair with arms. She tied me in because I couldn't balance on my own. She put the band with a stylus attached to it on my head. Then she pushed me up to an ancient black typewriter. I swear that typewriter was used by Thomas Edison. In fact, I thought then that he had made it himself, and still do!

Page 30

Miss Neff told me to turn the old clunker on. To our surprise I didquickly! She told me to type my name. I did. She told me to type the alphabet. I did! By this time, the speech therapist, the physical therapist and Mrs. Clanton had been called into the occupational therapy room to share in my victory over silence.

The people who were crowded into that stale, windowless OT room thought that my communication had gotten the best that it could have gotten. We were so wrong. Throughout the years my ability to communicate has been enriched and augmented by the computer age.

Although this adventure may be small compared with climbing Mount Everest or sailing the ocean on a raft, it was just as important. Through it God enabled me to conquer higher mountains and sail wider seas, now that he had helped me break the bounds of silence that held me for eleven years.

William L. Rush

Page 31

The Flight of the Red-Tail

When faced with a challenge, look for a way, not a way out.

David L. Weatherford

The hawk hung from the sky as though suspended from an invisible web, its powerful wings outstretched and motionless. It was like watching a magic show untilsuddenlythe spell was shattered by a shotgun blast from the car behind us.

Startled, I lost control of my pickup. It careened wildly, sliding sideways across the gravel shoulder until we stopped inches short of a barbed-wire fence. My heart pounded as a car raced past us, the steel muzzle of a gun sticking out the window, but I will never forget the gleeful smile on the face of the boy who'd pulled that trigger.

"Geez, Mom. That scared me!" Scott, fourteen, sat beside me. "I thought he was shooting at us! But look! He shot that hawk!"

While driving back to the ranch from Tucson along Arizona's Interstate 10, we had been marveling at a magnificent pair of red-tailed hawks swooping low over the

Page 32

Sonoran Desert. Cavorting and diving at breathtaking speeds over the yucca and cholla cacti, the beautiful birds mirrored each other in flight.

Suddenly, one hawk changed its course and soared skyward, where it hovered for an instant over the interstate as though challenging its mate to join in the fun. But the blast from the gun put an end to their play, converting the moment into an explosion of feathers dashed against the red and orange sunset.

Horrified we watched the red-tail spiral earthward, jerking and spinning straight

into the path of an oncoming eighteen-wheeler. Air brakes screeched. But it was too late. The truck struck the bird, hurling it onto the median strip.

Scott and I jumped from the pickup and ran to the spot where the stricken bird lay. Because of the hawk's size, we decided it was probably a male. He was on his back, a shattered wing doubled beneath him, the powerful beak open, and round, yellow eyes wide with pain and fear. The talons on his left leg had been ripped off. And where the brilliant fan of tail feathers had once gleamed like a kite of burnished copper against the southwestern sky, only one red feather remained.

"We gotta do something, Mom," said Scott.

"Yes," I murmured. "We've got to take him home."

For once I was glad Scott was in style with the black leather jacket he loved because when he reached for him, the terrified hawk lashed out with his one remaining weapon: a hooked beak as sharp as an ice pick. To protect himself, Scott threw the jacket over the bird, wrapped him firmly and carried him to the pickup. When I reached for the keys still hanging in the ignition, the sadness of the moment doubled. From somewhere high in the darkening sky, we heard the plaintive, high-pitched cries of the other hawk.

Page 33

"What will that one do now, Mom?" Scott asked.

"I don't know," I answered softly. "I've always heard they mate for life."

At the ranch we tackled our first problem: restraining the flailing hawk without getting hurt ourselves. Wearing welding gloves, we laid him on some straw inside an orange crate and slid the slats over his back.

Once the bird was immobilized we removed splinters of bone from his shattered wing, and then tried bending the wing where the main joint had been. It would only fold halfway. Through all this pain, the hawk never moved. The only sign of life was an occasional rising of the third lid over the fear-glazed eyes.

Wondering what to do next, I telephoned the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. When I described the plight of the red-tail, the curator was sympathetic. "I know you mean well" he said, "but euthanasia is the kindest thing."

"You mean destroy him?" I asked, leaning down and gently stroking the auburn-feathered bird secured in the wooden crate on my kitchen floor.

"He'll never fly again with a wing that badly injured," he explained. "He'll starve to death. Hawks need their claws as well as their beaks to tear up food. I'm really sorry."

As I hung up, I knew he was right.

"But the hawk hasn't even had a chance to fight," Scott argued.

Fight for what? I wondered. To huddle in a cage? Never to fly again?

Suddenly, with the blind faith of youth, Scott made the decision for us. "Maybe, by some miracle, he'll fly again someday," he said. "Isn't it worth a try?"

For three weeks the bird never moved, ate or drank. We forced water into his beak with a hypodermic syringe, but the pathetic creature just lay there staring, unblinking, scarcely breathing. Then came the morning when the

Page 34

eyes of the red-tail were closed.

"Mom, he's . . . dead!" Scott pressed his fingers beneath the matted feathers. I knew he was searching, praying for a heartbeat, and the memory of a speeding car and a smiling boy with a gun in his hands returned to haunt me.

"Maybe some whiskey," I said. It was a last resort, a technique we had used before to coax an animal to breathe. We pried open the beak and poured a teaspoon of the liquid down the hawk's throat. Instantly his eyes flew open, and his head fell into the water bowl in the cage.

"Look at him, Mom! He's drinking!" Scott said, with tears sparkling in his eyes.

By nightfall the hawk had eaten several strips of roundsteak dredged in sand to ease digestion. The next day, his hands still shielded in welding gloves, Scott removed the bird from the crate and carefully wrapped his good claw around a fireplace log where he teetered and swayed until the talons locked in. As Scott let go of the bird, the good wing flexed slowly into flight position, but the other was rigid, protruding from its shoulder like a boomerang. We held our breath until the hawk stood erect.

The creature watched every move we made, but the look of fear was gone. He was going to live. Now, would he learn to trust us?

With Scott's permission, his three-year-old sister, Becky, named our visitor Hawkins. We put him in a chain-link dog-run ten feet high and open at the top. There he'd be safe from bobcats, coyotes, raccoons and lobos. In one corner of the pen, we mounted a manzanita limb four inches from the ground. A prisoner of his injuries, the crippled bird perched there day and night, staring at the sky, watching, listening, waiting.

As fall slipped into winter, Hawkins began molting. Despite a diet of meat, lettuce, cheese and eggs, he lost

Page 35

most of his neck feathers. More fell from his breast, back and wings, revealing scattered squares of soft down. Pretty soon he looked like a baldheaded old man huddled in a patchwork quilt.

"Maybe some vitamins will help," said Scott. "I'd hate to see him lose that one red tail feather. He looks kinda funny as it is."

The vitamins seemed to help. A luster appeared on the wing feathers, and we imagined a glimmer on that tail feather, too.

In time, Hawkins's growing trust blossomed into affection. We delighted in spoiling him with treats like bologna and beef jerky soaked in sugar water. Soon, the hawkwhose beak was powerful enough to snap the leg bone of a jackrabbit or crush the skull of a desert rathad mastered the touch of a butterfly. Becky fed him with her bare fingers.

Hawkins loved playing games. His favorite was tug-of-war. With an old sock gripped tightly in his beak and one of us pulling on the other end, he always won, refusing to let go, even when Scott lifted him into the air and swung him around like a bolo. Becky's favorite game was ring-around-the-rosy. She and I held hands and circled Hawkins's pen, while his eyes followed until his head turned 180 degrees. He was actually looking at us backward!

We grew to love Hawkins. We talked to him. We stroked his satiny feathers. We had saved and tamed a wild creature. But now what? Shouldn't we return him to the sky, to the world where he belonged?

Scott must have been wondering the same thing, even as he carried his pet around on his wrist like a proud falconer. One day, he raised Hawkins's perch to twenty inches, just over the bird's head. "If he has to struggle to get up on it, he might get stronger," he said.

Noticing the height difference, Hawkins assessed the

Page 36

change from every angle. He scolded and clacked his beak. Then, he jumpedand missed, landing on the concrete, hissing pitifully. He tried again and again with the same result. Just as we thought he'd give up, he flung himself up at the limb, grabbing first with his beak, then his claw, and pulled. At last he stood upright.

"Did you see that, Mom?" said Scott. "He was trying to use his crippled wing. Did you see?"

"No," I said. But I'd seen something else, the smile on my son's face. I knew he was still hoping for a miracle.

Each week after that, Scott raised the perch a little more, until Hawkins sat proudly at four feet. How pleased he lookedpuffing himself up grandly and preening his ragged feathers. But four feet was his limit. He could jump no higher.

Spring brought warm weather and birds: doves, quail, roadrunners and cactus wrens. We thought Hawkins would enjoy all the chirping and trilling. Instead we sensed a sadness in our little hawk. He scarcely ate, ignoring invitations to play, preferring to sit with his head cocked, listening.

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul

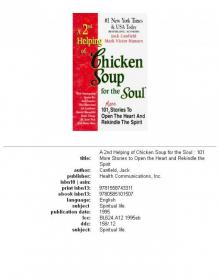

Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Chicken Soup for the Soul of America

Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul

Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues

Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul

Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers

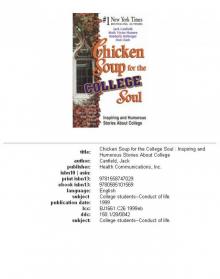

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Chicken Soup for the College Soul

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul

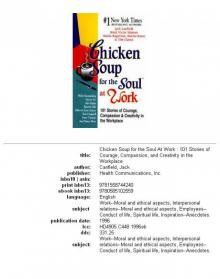

Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference

Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter

Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories

Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul Chicken Soup for the African American Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Soul 101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13

101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13 Christmas Magic

Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs Chicken Soup for the Country Soul

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul)

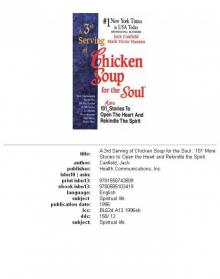

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul) A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul The Book of Christmas Virtues

The Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Little Souls

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II