- Home

- Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Page 23

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Read online

Page 23

It reminded him of the time that Dick Schaap (a sportswriter for New York magazine) wrote an article entitled “The Ten Most Overrated Men in N.Y.C.” He told me that as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, his name headed the list. George invited the other nine men, the nervous author and several ambassadors to a reception honoring “The Overrated.” It was a great party.

The newspapers and the Bushes had lots of fun with The Washingtonian article. George immediately came to my defense. Bar was a little quieter. After what she had whispered to me that first night, I guess she felt this was one battle she should stay out of. The editors of The Washingtonian even apologized and sent me some marvelous dog biscuits. George accepted their apology. He wrote the editor of the guilty magazine: “Dear Jack: Not to worry! Millie, you see, likes publicity. She is hoping to parlay this into a Lassie-like Hollywood career. Seriously, no hurt feelings; but you are sure nice to write. Arf, arf for the dog biscuits—Sincerely, George Bush.” Easy for the President to accept the apology. I did not.

It was bad enough to have my face on the cover, beside which they had written, “Our Pick as the Ugliest Dog: Millie, the White House Mutt,” but the picture they had inside was taken the very afternoon of my delivery. Show me one woman who could pass that test, lying on her side absolutely “booney wild” (family expression for undressed) on the day she delivered six babies! I also objected to the word “mutt.” I am a blueblood through and through.

After The Washingtonian attack we got lots of letters. Many came to my defense. There were letters to the editor, and many letters sent directly to the White House. I guess the most pleasing message of all came directly from the office of Senator Bob Dole, who personally brought the following press release to the White House:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

LEADER: WASHINGTONIAN ATTACK ON FIRST DOG MILLIE:

AN “ARF” FRONT TO DOGS EVERYWHERE

WASHINGTON—CALLING IT AN “ARF” FRONT TO DOGS EVERYWHERE, LEADER, FIRST K-9 ASSISTANT TO SENATE REPUBLICAN LEADER BOB DOLE (R-KS) SAID TODAY THAT THE WASHINGTONIAN MAGAZINE WAS BARKING UP THE WRONG FIRE HYDRANT WHEN IT PICKED FIRST DOG MILLIE AS WASHINGTON’S UGLIEST DOG IN ITS CURRENT “BEST & WORST” LIST.

“I TALKED WITH MILLIE ABOUT THIS TODAY,” LEADER SAID, “AND ADVISED HER TO START USING THE WASHINGTONIAN TO PAPER-TRAIN HER PUPPIES.”

LEADER ANNOUNCED HE’S FORMING A NEW ORGANIZATION CALLED P.A.W.S.—WHICH STANDS FOR POOCHES AGAINST WASHINGTON SMEARS.

“WHATEVER HAPPENED TO ALL THIS ‘MAN’S BEST FRIEND’ STUFF I’VE BEEN HEARING ALL THESE YEARS? IF THE EDITORS OF THE WASHINGTONIAN KEEP UP THESE DOGMATIC ATTACKS, THEY HAD BETTER WATCH THEIR STEP— LITERALLY WATCH THEIR STEP,” LEADER SAID.

“AS FIRST DOG, MILLIE HAS SET A GREAT EXAMPLE FOR MILLIONS OF AMERICAN DOGS. SHE IS RAISING A FAMILY, DOESN’T STRAY FROM THE YARD, AND DOES HER BEST TO KEEP HER MASTER IN LINE. IT’S JUST NOT RIGHT FOR HER TO BE HOUNDED LIKE THIS.

“LET’S MAKE NO BONES ABOUT IT. DOGS EVERYWHERE ARE WHINING ABOUT THIS. LET IT BE KNOWN, WE WON’T SIT FOR IT.”

Millie Bush

As dictated to Barbara Bush

Barney

Mary Guy figured that becoming a national celebrity was probably about as much as a squirrel could hope to achieve in one lifetime. But Barney is not your average squirrel.

Mary has a bottled water business in Garden City, Kansas. She is also a known animal lover. One day in August of 1994, one of her customers showed her an orphaned baby fox squirrel that he had found. When he asked if she could care for it, she felt she had to at least give it a try.

It so happened that a week earlier, Mary’s cat, Corky, had had four kittens. Mary’s husband, Charlie, suggested they try adding the squirrel to the litter of kittens—and it worked! Barney (named by a grandson after a particular purple dinosaur) was not only adopted by Corky, he was accepted as a sibling by all four kittens. He became especially close with one feline sister, Celeste.

Some of the Guys’ guests thought this cat/squirrel family was so adorable that they contacted the local newspaper about it. The paper ran a story with a photo of the mother cat nursing her four kittens and Barney under the headline: “One of these kittens seems sort of squirrelly.”

The unusual story was picked up by the Associated Press and sent to newspapers all over the country. As a result, Mary received calls and letters from all over the country, and even Canada, by people who were impressed with the story and picture. Barney was a celebrity!

Unfortunately, there was a downside to Barney’s fame.

The article was seen by employees of the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks. A state official contacted the Guys and told them that it is illegal to keep a squirrel as a pet in the state of Kansas. They would have to return Barney to the wild.

Mary was thunderstruck. Not only had she become attached to her unusual pet, she feared for his life if he was turned loose. He had no fear of cats—he’d been raised by one! But squirrels are rodents and cats are natural enemies of rodents. If Barney was turned loose, he’d be lunch for the first stray cat he met. She explained this to the authorities, but to no avail. The law’s the law.

“Well, ma’am,” suggested one officer, “if you buy a hunting license, you can legally keep him until the end of squirrel season. It runs until December 31.”

It was a temporary solution, but Mary hurried out to pay the thirteen dollars for a hunting license.

Mary grieved as the end of the year approached. She had come to truly love the mischievous little guy and was certain that turning him loose was tantamount to a death sentence.

Also, by this time, all of the kittens had been adopted except Celeste; and she and Barney were now best friends. They played together, slept together and chased each other all over the house. If Mary separated them, Celeste wailed miserably. And Barney showed not the slightest interest in life in the great outdoors.

Mary again approached the newspapers. Perhaps the same notoriety that had landed Barney in this mess could lead to a solution.

The story of Barney’s plight went out over the Associated Press wires. By early December, Mary was deluged with calls and letters from all over the country offering their prayers and moral support. Some callers who lived in states with differing laws even offered to take in both Barney and Celeste.

The Wildlife and Parks Department also received calls and mail from around the country. Not wanting to look heartless, they suggested that Barney might be released at the Garden City Zoo’s park. The Kansas Attorney General called Mary and suggested that she give Barney to a “rehabilitator” who would teach him to survive in the wild before releasing him.

Still, Mary feared for the safety of her beloved pet—and knew he didn’t want to leave his happy life any more than she wanted to lose him.

As New Year’s Eve approached, the Guys saw one slim chance. The new year would bring a new administration into the Kansas statehouse. Mary arranged for friends who were invited to the new governor’s inaugural celebration to take information about Barney with them.

One of the first acts of the Kansas governor’s office in 1995 was to issue the Guys a special permit to keep their squirrel.

And so Barney became the first squirrel in history to not only become a national celebrity, but to receive a pardon from the governor.

No, not your average squirrel at all.

Gregg Bassett

President, The Squirrel Lover’s Club

Mousekeeping

Until a certain sunny morning in early September, I had never sought the company of mice. On that day, my husband, Richard, called me out to the barn of our Rhode Island farm, where I found him holding a tin can and peering into it with an unusual expression of foolish pleasure. He handed me the tin can as though it contained something he had just picked up at Tiffany’s.

Crouched at the bottom was a young mouse, not much bigger than a bumblebee. She stared up with eyes like polished seeds. She was a beautiful little creature a

nd clearly still too small to cope with a wide and dangerous world.

Richard had found her on the doorstep. When he picked her up, he thought the little mouse was done for. By chance he had a gumdrop in his pocket, and he placed the candy on his palm beside the limp mouse. The smell acted as a stimulant. She flung herself upon the gumdrop, ate voraciously and was almost instantly restored to health.

Richard made a wire cage for Mousie, as we now called her, and we made a place for her on a table in the kitchen. I watched her while I peeled vegetables. I found myself fascinated by her—I had no idea there were so many things to notice about a mouse.

Her baby coat was a dull, gun-metal gray, but it soon changed to reddish brown with dark gray anklets and white feet. I had thought the tails of mice were hairless and limp. Not so. Mousie’s tail was furred, and rather than trailing it behind like a piece of string, she held it up quite stiffly. Sometimes the tail rose over Mousie’s back like a quivering question mark.

She cleaned herself like a cat. Sitting on her small behind (she could have sat on a postage stamp without spilling over), she licked her flanks, then moistened her paws to go over her ears, neck and face. She would grasp a hind leg with suddenly simian hands while she licked the extended toes. For the finale she would pick up her tail and, as though eating corn on the cob, wash its length with her tongue.

Mousie became tame within a few days. She nibbled my fingers and batted them with her paws like a playful puppy. She liked to be petted. If I held her in my hand and rubbed gently with a forefinger, she would raise her chin, the way a cat will, to be stroked along the jawbone. Then she would lie flat on her back in the palm of my hand, eyes closed, paws limp and nose pointed upward in apparent bliss.

Our little friend slept in a plastic Thermos cup, lined with rags that she shredded into fluff as soft as a down quilt. After a while I replaced the cup with half a coconut shell that I inverted, cutting a door into the lower edge. It was a most attractive mouse house, quite tropical in feeling. Mousie stuffed it from floor to ceiling with fluff.

The cage was equipped with twigs for a perch and an exercise wheel on which Mousie traveled many a league to nowhere. Her athletic ability was astounding. Once I put Mousie in an empty garbage pail while I cleaned the cage. She made a straight-upward leap of fifteen inches, nearly clearing the rim.

Mousie kept food in a small aluminum can we had screwed to the wall of the cage. Richard and I called it the First Mouse National Bank. If I sprinkled bird seed in the cage, Mousie worked diligently to transport it, stuffing the seeds in her little cheeks for deposit in the bank.

Though Mousie kept busy, I feared that her life might be lonely. I asked a biologist I knew for help. He’s the one who determined Mousie’s sex (to a lay person, the rear end of a mouse is quite enigmatic), and he provided a male laboratory mouse as a companion.

The new mouse had a stout body, hairless tail and a mousy smell—unlike our Mousie, who was seemingly odorless. I named him Stinky and with some misgivings put him in Mousie’s cage.

Stinky lumbered about, squinting at nothing in particular, until he stumbled across some of Mousie’s seeds. He made an enthusiastic buck-toothed attack on these goodies. Flashing down from her perch, Mousie bit Stinky’s tail. He continued to gobble. Disgusted, Mousie went to bed.

From this unpromising start, a warm attachment bloomed. The two mice slept curled up together. Mousie spent a great deal of time licking Stinky, holding him down and kneading him with her paws. He returned her caresses, but with less ardor. He reserved his passion for food.

One day as an experiment, I put Mousie’s food bank on the floor of the cage. Stinky sniffed at the opening. Mousie watched, whiskers quivering, and I had the distinct impression of consternation on her face. With a quickness of decision that amazed me, Mousie seized a wad of bedding, stuffed it into the bank, effectively corking up her treasure. It was a brilliant move. Baffled, Stinky lumbered away.

In spite of their ungenerous behavior toward each other, I felt that Stinky made Mousie happy. Their reunions after being separated were always joyous, with Mousie scrambling all over Stinky and just about licking him to pieces. Even stolid old Stinky showed some excitement.

I wasn’t aware when Stinky became ill. But one day after about a year, I saw Mousie sitting trembling on her branch when she should have been asleep. I looked in the cage and found Stinky stone-cold dead.

Alone the rest of her days, Mousie lived a total of more than three years. That, I believe, is a good deal beyond the span usually allotted to mice. She showed no sign of growing old or feeble. Then one day, I found her dead.

As I took her almost weightless body in my hand and carried it out to the meadow, I felt a genuine sadness. She had given me much. She had stirred my imagination and opened a window on a Lilliputian world. Beyond that, there had been moments when I felt contact between her tiny being and my own. Sometimes when I touched her lovingly and she nibbled my fingers in return, it felt as though an affectionate message was passing between us.

I put Mousie’s body down in the grass and walked back to the house. I was sad, not for Mousie, but for me. The size of a friend has nothing to do with the void he or she leaves behind. I knew I would miss my littlest pet.

Faith McNulty

The Cat and the Grizzly

Cats seem to go on the principle that it never does any harm to ask for what you want.

Joseph Wood Kruth

“Another box of kittens dumped over the fence, Dave,” one of our volunteers greeted me one summer morning. I groaned inside. As the founder of Wildlife Images Rehabilitation Center, I had more than enough to do to keep up with the wild animals in our care. But somehow, local people who didn’t have the heart to take their unwanted kittens to the pound often dumped them over our fence. They knew we’d try to live-trap them, spay or neuter them, and place them through our network of approximately 100 volunteers.

That day’s brood contained four kittens. We managed to trap three of them, but somehow one little rascal got away. In twenty-four acres of park, there wasn’t much we could do once the kitten disappeared—and many other animals required our attention. It wasn’t long before I forgot completely about the lost kitten as I went about my daily routine.

A week or so later, I was spending time with one of my favorite “guests”—a giant grizzly bear named Griz.

This grizzly bear had come to us as an orphaned cub six years ago, after being struck by a train in Montana. He’d been rescued by a Blackfoot Indian, had lain unconscious for six days in a Montana hospital’s intensive care unit, and ended up with neurological damage and a blind right eye. As he recovered, it was clear he was too habituated to humans and too mentally impaired to go back to the wild, so he came to live with us as a permanent resident.

Grizzly bears are not generally social creatures. Except for when they mate or raise cubs, they’re loners. But this grizzly liked people. I enjoyed spending time with Griz, giving him personal attention on a regular basis. Even this required care, since a 560-pound creature could do a lot of damage to a human unintentionally.

That July afternoon, I approached his cage for our daily visit. He’d just been served his normal meal—a mix of vegetables, fruit, dog kibble, fish and chicken. Griz was lying down with the bucket between his forepaws, eating, when I noticed a little spot of orange coming out of the blackberry brambles inside the grizzly’s pen.

It was the missing kitten. Now probably six weeks old, it couldn’t have weighed more than ten ounces at most. Normally, I would have been concerned that the poor little thing was going to starve to death. But this kitten had taken a serious wrong turn and might not even last that long.

What should I do? I was afraid that if I ran into the pen to try to rescue it, the kitten would panic and run straight for Griz. So I just stood back and watched, praying that it wouldn’t get too close to the huge grizzly.

But it did. The tiny kitten approached the enormous bear and let out a purr

and a mew. I winced. With any normal bear, that cat would be dessert.

Griz looked over at him. I cringed as I watched him raise his forepaw toward the cat and braced myself for the fatal blow.

But Griz stuck his paw into his food pail, where he grabbed a piece of chicken out of the bucket and threw it toward the starving kitten.

The little cat pounced on it and carried it quickly into the bushes to eat.

I breathed a sigh of relief. That cat was one lucky animal! He’d approached the one bear of the sixteen we housed that would tolerate him—and the one in a million who’d share lunch.

A couple of weeks later, I saw the cat feeding with Griz again. This time, he rubbed and purred against the bear, and Griz reached down and picked him up by the scruff of his neck. After that, the friendship blossomed. We named the kitten Cat.

These days, Cat eats with Griz all the time. He rubs up against the bear, bats him on the nose, ambushes him, even sleeps with him. And although Griz is a gentle bear, a bear’s gentleness is not all that gentle. Once Griz accidentally stepped on Cat. He looked horrified when he realized what he’d done. And sometimes when Griz tries to pick up Cat by the scruff of the cat’s neck, he winds up grabbing Cat’s whole head. But Cat doesn’t seem to mind.

Their love for each other is so pure and simple; it goes beyond size and species. Both animals have managed to successfully survive their rough beginnings. But even more than that, they each seem so happy to have found a friend.

Dave Siddon

Founder, Wildlife Images Rehabilitation Center

As told to Jane Martin

Fine Animal Gorilla

Those of us who study apes have always known that gorillas are highly intelligent and communicate with each other through gestures. I had always dreamed of learning to communicate with gorillas. When I heard about a project in which other scientists tried to teach a chimpanzee American Sign Language (ASL), I was intrigued and excited. I thought ASL might be the perfect way to talk to gorillas because it used hand gestures to communicate whole words and ideas. As a graduate student at Stanford University, I decided to try that same experiment with a gorilla. All I had to do was find the right gorilla.

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Chicken Soup for the Soul of America

Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul

Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues

Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul

Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers

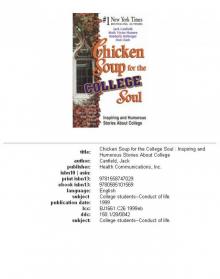

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Chicken Soup for the College Soul

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference

Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter

Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul

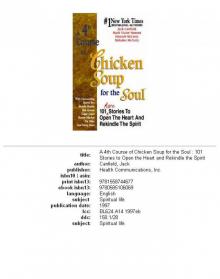

Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul

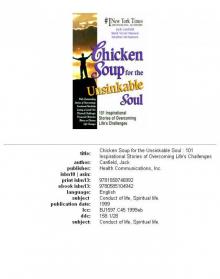

A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories

Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul Chicken Soup for the African American Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Soul 101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13

101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13 Christmas Magic

Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs Chicken Soup for the Country Soul

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul)

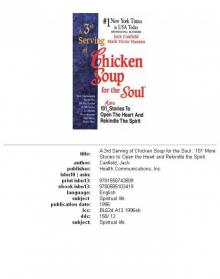

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul) A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul The Book of Christmas Virtues

The Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Little Souls

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II