- Home

- Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Page 2

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Read online

Page 2

On the starting date I woke with excitement, then gasped at the dramatic weather changes. Heavy snow covered the trees and roads. Fallen tree branches covered portions of the streets as far as I could see. I had slept through the worst ice storm in the history of our county. The radio recited a long list of closings. I was sure my school was among them, but I called to confirm. “No, we are open for classes,” the receptionist informed me. My father agreed to take me and came without a murmur.

We gathered in one classroom sharing our nursing aspirations. When I explained how I learned about the program, everyone was amazed that I started the same year that I applied. “I’ve been on the waiting list for two years!” was the common response from others. This confirmed what I already knew: this career move was orchestrated by God.

School demanded rigorous discipline. My children were ten months, two, and four. I had two in diapers and one in preschool. After a full day at school, I looked forward to spending time with them. By the time I got them fed, bathed, and prepared for bed, I was exhausted. I gathered my thick medical texts to prepare for study and was asleep in seconds. It was God’s grace and my thirst for knowledge that enabled me to earn good grades.

Things went well until the ninth month when I experienced medical problems and my doctor recommended bed rest. There was no way for me to miss classes and maintain passing grades.

“Take some time off to get better and return next year,” the director said. I was devastated, having anticipated graduation in only three months. I had invested too much to give up and was ready for my struggling to end.

With regained health I returned the following year. I was appalled to learn that only three months’ credit was granted for the previous nine months of toil. I pushed my anger aside and forged ahead. I worked harder than ever for nine months and I graduated, with my family smiling proudly in the audience.

After passing the state-mandated test, I became a licensed practical nurse. I submitted applications to all the local hospitals. When I talked to other classmates, they all had dates scheduled for orientation. I had not heard a thing. I debated whether to call and check on my application. Hesitantly, I phoned the hospital where I really wanted to work. “I’m wondering if you’ve been trying to call me . . . I’m in and out often . . .”

“Yes we have,” the human resource staffer responded.

Thus began my nursing career.

A few years later I entered college to become a registered nurse. That was twenty-three years ago and I thank God every day for calling me to serve others in this way.

Recently, as I cared for my patient, a weary-looking young woman visitor asked, “Is it hard to be a nurse?”

I detected a glimmer of hope in her eyes.

I smiled eagerly. “Let me tell you about becoming a nurse . . . ”

Jeri Darby

Pilar

Even as a small child, I remember wanting to be a nurse. I dreamed of being all dressed in starched white with a cap perched neatly on my head. I always had a little plastic nurse bag, filled with the tricks of the trade. I nursed all my dolls, teddy bears, pets, and even my brother and sister when I could corner them to play with me.

Then one person seemed to seal this desire in my life. When I was eight, my mother was seriously injured and spent a month in a hospital that was forty miles from our little ranching community. She spent part of the critical time in a burn center and then was moved to a medical unit in a tall red brick building. We missed Mama so, but neither my brother, sister, nor myself were fourteen yet, so we weren’t allowed to visit.

Dad took us to the hospital and we stood on the lawn outside to see a blurred wave from our mother through a high-up window as she lay in her bed.

Dad assured us that a special nurse was taking care of Mom. Pilar was a gentle person who tenderly cared for Mom’s broken body. Then she’d sit at her bedside and read the Bible to her when my mother could not hold a book for herself. She would push the bed nearer the window so my mom could see us better on days we came to “visit.” But Mom missed her kids and her kids didn’t understand.

One day we went to town with Dad on some errands and planned to stop and wave up at my mother. We stepped up to the brick building and my dad went inside to tell Pilar we were waiting for a glimpse of Mom through the window. But instead of going into my mother’s room, Pilar took off down the back stairway, came outside to the three of us, and said, “Be very quiet and follow me.”

We went back to the stairs and snuck up to the proper floor. Pilar opened the door and glanced down the hall. Like a protective mother hen, she expertly and quietly guided us hurriedly into my mother’s room and shut the door, leaning against it like a guard. And suddenly, after weeks of only seeing her wave, there was my mom. She was in slings and bandages, but we could touch her and feel her mothering hands. I’m sure we were much too loud in our excitement, but it was too good to hold inside. My dad stood quietly and blew his nose.

The next week, we were huddled on the lawn under Mom’s window when Pilar appeared again and repeated the wonderful words, “Follow me!”We tiptoed up the back staircase and she secretly herded us into Mama’s room. There on the bedside stand sat a chocolate cake with fudge frosting. We giggled and munched with Dad and Mom and ate until it was gone.

Eventually, my mother came home. She talked often through the years about Pilar, and I realized what an impact she had made on my mother and on me.

She was exactly the nurse I wanted to be.

Terry Evans

Memories of Polo

Death may be the greatest of all human blessings.

Socrates

Every time I smell the sweet pungent fragrance of Polo aftershave, memories take me back to the trauma intensive care unit. Almost twenty years of nursing and uncountable numbers of patients fade away when that sweet aroma floods my senses. Once again I am standing at Roy’s bedside.

Nursing was new to me then, but the unit wasn’t. I had worked as a nurse assistant at night and attended nursing school clinicals in the unit during the day. New graduates weren’t usually hired into the ICU, but to me it was home and, with the staff’s blessings, my first job as a graduate R.N.

I had little experience with death. It wasn’t discussed much in school. The doctors acted as if it was a dragon to be defeated at all costs. The experienced nurses told me death wasn’t the enemy. I didn’t really understand what they were trying to say.

Until Roy.

What he taught me about death brings a hot rush of tears as I write this. But nurses aren’t supposed to cry, are they?

“So sad,” Donna told the charge nurse as I walked up. Twenty years of nursing had etched a permanent look of concern on her grandmotherly old face. “You’re young, Sharon,” she said. “Maybe Roy will talk to you.”

“Why is he here?” I asked.

“Motorcycle accident,” she replied. “I’ll watch your patients, you go visit Roy.”

Time hasn’t dampened the rush of raw teenage emotion that met me at the door to Roy’s room. The tracheostomy tube didn’t affect his ability to communicate the anger and frustration he felt.

“I hate this place. I hate you. I want to go home,” he mouthed as I walked in.

His greasy, matted hair was plastered against his scalp. His thin, gangly body was lost in a jumble of wrinkled sheets and tubes. His eyes were dark brown and challenging. Fear and pain mixed in with his message, but what fifteen-year-old boy would admit that? His face was covered with acne and a sparse, peach-fuzz trace of beard. He reminded me of the abandoned puppy I had found on the side of the road. He also reminded me of my cousin Mark who’d been so excited and proud about the whiskers he had grown (about twelve hairs as I recall).

I looked seriously at Roy. “You sure can’t go out looking like this,” I said. “You need a bath and a shave, or are you planning on growing a beard?”

Roy looked at me wide-eyed. He rubbed his hand across his chin and grinned. The way his ex

pression changed told me he was sure his beard must be thick . . . a man’s beard.

“A bath and a shave,” he mouthed. “I use Polo aftershave,” he informed me proudly.

“Polo it is then.”

The bath, shave, clean sheets, and pain medicine sealed our friendship. Bathtime became our nightly routine. Roy would drift off to sleep with the sweet smell of Polo filling his dreams with other places and situations far removed from the reality of his hospital room. Polo’s aroma lingered on my uniform and silently followed me as I worked.

Roy’s accident was a tragedy. He was from a small mountain town far from the hospital. His friend had a new motorcycle that Roy wanted to try. His dad said no, but Roy, in typical teenage style, rode it anyway, wrecking almost immediately. His chest was crushed against a telephone pole.

The left lung was unrepairable, the right lung damaged. Angry with his son and devastated by the doctors’ dire predictions, Roy’s dad refused to visit. Roy’s mom didn’t drive.

The sweet smell of Polo and the sound of MTV filled Roy’s room on my night shift. He loved baseball and bragged about his school team. We decorated his room with baseball posters and balloons. As he became more cooperative, the day shift began to spoil him too. Roy told me he had a younger sister.We couldn’t replace his family, but we were determined to make sure he felt special and loved.

The last week of Roy’s short life was a blur of activity as doctors and nurses worked to save him.Nurses don’t cry, I told myself as I charted on Roy’s last night.My tears fell anyway, ignoring my orders to keep a professional perspective.

“I’m not assigning you patients tonight,” the charge nurse said in report. “Roy has been asking for you and there is not much we can do now. He’s not expected to live until morning.”

“Does he know?” I asked, blinking back tears.

No one answered me.

Roy and I had never talked about death. We both were still young enough to think that death only happened to someone else.

As Roy began to die, he held my hand so tightly my fingers became numb. He begged me not to leave his side. I held his hand and whispered about baseball and a place called heaven where he would be free of pain, while my colleagues worked frantically, and he slowly suffocated.

“Good-bye Roy,” I told him as I bathed his now cold body and splashed Polo on his face one last time. As the sweet aroma filled his room, I began to feel better. Roy taught me what nursing school didn’t.

Sometimes death is the cure, and good nurses do cry.

Sharon T. Hinton

Nurse Nancy

The man who has confidence in himself gains the confidence of others.

Hasidic Saying

My strong sense of what I wanted to be when I grew up came from memories of my first five years of childhood spent in an orphanage in Ohio. I fondly remember a nurse who was my friend there. She was my “Angel of Mercy,” my real-life Nurse Nancy. She wore a white hat, starched white uniform, tight white hose, white shoes, and a blue cape. How I loved my nurse. She told me stories, tickled me, made me giggle and laugh, and filled my bath full of huge colored bubbles. My nurse was my hero and I wanted to be just like her.

When I was blessed by being adopted, my parents must have known my devotion to this nurse. I arrived at my new home to find a gift placed in my very own bed—a nursing outfit: a white uniform, cap, and cape, plus shots, Band-Aids, and a stethoscope. Everything I would need to fulfill my role as Nurse Nancy.

Remember Golden Books? As a child I treasured them. My favorite was titled, no surprise, Nurse Nancy. This treasured book read, “Nancy liked to play with dolls. She liked to play mother. Best of all, she liked to play nurse.” That was me as a child. I bandaged my dolls, my dog, my brother! Anyone who would sit long enough was nursed. I gave M&Ms to my patients for pills, which, needless to say, kept me busy playing nurse. All the neighborhood children lined up for my care. I, like Nurse Nancy, kept logbooks with recorded names of my patients, such as Baby 1, Baby 2. Listed diseases included, but were not limited to, sick, fever, cold, and measles.

Make-believe days have passed. I have been a “real” nurse for thirty-plus years.

Of all my years as a nurse, the greatest blessing this career gave me happened sixteen years ago when my husband and I spent three weeks in Romania waiting to adopt our twin sons. Because they were six weeks premature, we had to wait for them to gain weight before we could take them home. The doctor was reluctant to release these tiny babies to new, inexperienced parents. Needless to say, we were eager to return home with our twins.

One day as I talked to their nurses, I thanked them for their care. Despite our language barrier, I was able to see and feel the genuine concern they had for our soon-to-be sons. I witnessed again the reputation nurses have for caring and compassion . . . as far-reaching as an orphanage in Ohio to an orphanage in Romania. In this conversation, I revealed that I, too, was a nurse. At that moment the nurses left the room.

Shortly thereafter, through the doors burst an exuberant doctor, and in his marked Romanian accent he called out, “Why did you not tell me you were a nurse? I release your sons to your care today, Nurse Nancy!”

Nancy Barnes

Welcome to War

War is a series of catastrophes that results in a victory.

Georges Clemenceau

I was twenty-two years old when, on a whim, I volunteered to go to Vietnam. It was the autumn of 1970 and, despite my age, I was considered an experienced pediatric nurse, to be assigned to the U.S. Army’s only children’s hospital in Quang Tri.

It was a long flight overseas with only a brief stop in Hawaii. Some soldier, barely old enough, offered to buy me a drink at the airport bar. I was so impressed with the fun, the camaraderie, and just plain courtesy I observed on that trip over. A naturally shy person, I was overwhelmed by how many men came over to meet me. They made me feel as if they were honored to be in my presence because I had volunteered to care for them. All throughout my weeks of basic training I had noticed the near reverence with which we nurses were treated.

I landed in Vietnam at night, at the Bien Hoa airstrip outside of Saigon. I’ll never forget that night, my first introduction to warfare. From the bus we heard thundering guns, saw the eerie lightning, and witnessed the extreme poverty of the war’s victims. They huddled in cardboard huts, their fragile homes advertising corporate giants like General Electric, Ford, and Westinghouse.

I wondered what was in store for me.

A few days later I was flown north, to within five miles of the demilitarized zone separating South Vietnam from our enemy, the Communist Republic of North Vietnam. The airport near the hospital where I was to work was a busy place; military jets were taking off all around me. I had never felt quite so alone. Then I heard someone call “Lieutenant Burghart?” I found myself surrounded by several young American soldiers from the 18th surgical hospital and the 237th Dust off unit. They had a tradition of greeting new nurses with a helicopter ride, carrying them across the street.

However, one man in the Dust off unit scoffed, “Flying across the street to pick up a nurse is a waste of time!”

Another whispered to me, “Private Geoffrey Morris’s unit just lost three helicopters and their crews.”

No wonder he didn’t have much room for frivolity in war.

It wasn’t long before I heard from Geoff Morris again. He was strolling down the hospital corridor soon after my arrival and heard me asking someone to donate blood for one of my young patients. When I was unsuccessful, he watched as I took blood from my own arm for the child.

Thirty-five years have gone by since then, and Geoff still likes to tell our four children that that was the moment he fell in love with me.

Emily Morris

Confessions of a CNO

Remember this—that there is a proper dignity and proportion to be observed in the performance of every act of life.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

As I

connect with all of the wonderful nurses that I have had the privilege to work with over thirty-five years in administration, and ask them why they became nurses, the answers are inevitably similar. “I want to help people,” “I wanted to be a nurse like my mom,” “I want to feel valuable to the greater good or the community.” My journey to nursing was not so altruistic. I must confess, I wanted to be a dancer, not a nurse. My goal was to live and dance professionally in New York City. A friend who was studying nursing convinced me that if I took a couple of years off from dancing to obtain my nursing degree, I could have a good job between shows and I wouldn’t have to wait tables like other striving actresses and dancers. I thought her suggestion was a great idea, even though I felt that my place in life was to make people happy by entertaining them. But when I began working in the hospital as a nurse, my life was transformed.

I realized that as a performer I made people happy for a few minutes but I did not have a meaningful impact on their lives. Nurses cared about people, whereby most performers cared about themselves and their next job. It began to frustrate me to observe the value that society continually placed on performers as evidenced by the money and fame that they received. It undervalued the “true heroes”—the nurses.

I knew that I would never leave nursing to dance again when I began working in critical care as a new nurse. I received the call from the emergency department that we were getting a level-one trauma patient. A student nurse on her way home from a study group totaled her car close to our hospital. In those days, very long ago, seat belts were not promoted as they are today, and she was ejected out the front window, under the car, which then exploded. Surprisingly, she did not suffer severe burns, but her skull was crushed. Soon after surgery, brain activity ceased. Her mom, tormented by the turn of events, truly believed that her daughter was going to recover. Staff members did not share the same level of optimism but supported the family in their decision to maintain life support until they were ready to make that difficult decision. Determined that she would recover, her mom refused the option for organ donation. She did agree, however, that if her daughter arrested we would not “code” her or perform unnecessary heroics.

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Chicken Soup for the Soul of America

Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul

Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues

Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul

Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers

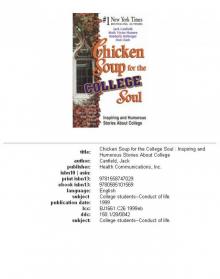

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Chicken Soup for the College Soul

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference

Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter

Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories

Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul Chicken Soup for the African American Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Soul 101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13

101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13 Christmas Magic

Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs Chicken Soup for the Country Soul

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul)

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul) A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul The Book of Christmas Virtues

The Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Little Souls

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II