- Home

- Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Page 13

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Read online

Page 13

“Yeah! Everybody needs help now and then,” I told him.

Overhearing the conversation the guy caught the amount of money that the writer needed. My guest said he made more than that in a week playing in Oklahoma.

“If that’s the case, you’d better get on back to Oklahoma. You’ll never make that kind of money playing the clubs in Nashville. I’ve got this saying: ‘We create music in Nashville, and we sell it in Texas.’ You can certainly include Oklahoma in there, too,” I added.

The new guy laughed, “Well I just can’t believe that. What if I bring my whole band down here?”

“How many is in your band?” I asked.

“Five.”

“Well,” I said, “you and five other guys will starve to death in Nashville,” I predicted.

Sensing that I’d offended my guest, I tried to make amends by telling him, “Those are just the facts in this town. If you want to come here and write, if you want to make it as an artist, it’s going to be tough. However, I’ll be glad to help you. I’ll see you at 9:00 tomorrow morning right here in my office. Since my friend, Rod, sent you to me, I’m going to do what I can to help you.” Later, I learned that my guest had the use of Rod’s personal credit cards so the guy could get to Nashville—that’s how much Rod believed in his potential. “You be here at 9:00, and I’ll help you find a place to live,” I promised.

Well, at 9:00 the next morning, the Oklahoma guy didn’t show. I waited ’til about 10:30 before I called Rod and asked if he’d seen him. “No, I thought he was with you,” was the response.

I told Rod the guy was suppose d to be with me. That bothered Rod because, well, this guy always kept his appointments. That afternoon, Rod called to let me know what had happened. His guy was all upset with me and was headed back to Oklahoma. I explained that all I did was just tell him the truth. “Man, if he can’t take the truth, well, I’m sorry. I just told him the way things are in a detailed story of what has to be done to make it in Nashville.”

That was the end of it—or so I thought. About a year later, this Oklahoma guy came back. But instead of seeing me, he walked right past my office and down the hall to talk with my associate. Soon after, the two of them struck a deal. I guess the guy didn’t particularly want to see me. A few months later, this associate left ASCAP and opened a publishing company with the guy from Oklahoma.

Several months later, I attended a “Writer’s Night” at Nashville’s Blue Bird Café. To my surprise, the Oklahoma guy was filling in for a writer who didn’t show up. A few months later, he was signed to Capitol Records and recorded his first album. At that time, the president of Capitol Records was a friend of mine named Joe Smith. I sent Joe the guy’s advance tape and told him to give special attention to this young man. I told Joe this guy was a friend of mine, and he’s going to be a “monster” artist. Joe took my advice. Capitol Records spent a lot of money on the new artist and did everything necessary to help him become a huge success.

After this guy hit the top, he told everybody who would listen that everything I’d said had been true. Since then, he has thanked me many times. Not long ago, the now-legendary country star and I got together. He said, “Merle, you remember that first meeting we had in Nashville? Has it already been ten years? I’ll never forget it!”

This story just goes to show that it takes more than being friends—it takes talent, persistence, focus and hard work—to survive and become a superstar in the entertainment business.

Just ask my friend, Garth Brooks.

Merlin Little field

In the Footsteps of a Good Man

If you’re dedicated, if it’s something that lives and breathes in your heart, then you’ve simply got to go ahead and do it.

Rodney Crowell

I always knew I was the different one in my family. They all seemed normal. Whereas, from the day I picked up a guitar, I was obsessed. Before I was ten years old, I began to eat, sleep and dream bluegrass and country music. I had every album and I could play along. My hero of heroes was Lester Flatt. By the time I was eleven, I knew I wanted to be just like him.

When I was twelve years old, in 1971, I got a friend to take me to Bill Monroe’s festival in Bean Blossom, Indiana. The whole thing was magic, but nothing mattered as much as the fact that Lester Flatt would be playing in person. I had the concert schedule memorized, and before it was time for Lester Flatt to play, I found his bus. It was a vision in diesel. It looked like a rolling billboard, painted with “Lester Flatt and the Nashville Grass Sponsored by Martha White Flour.”

When Lester Flatt came out, the speech I’d planned for about seven years got lost inside of me. It was all I could do to ask for an autograph. As I followed him on the long walk to the stage, I noticed the way he cocked his hat on his head—and the effect he had on the campers. As he walked through, they sort of stood straighter. It was like the effect of a preacher walking through a poker game.

I followed in his wake, knowing I was walking in the footsteps of a good man.

I left the festival even more on fire with the thrill of music. That summer I spent as much time as I could around local musician Carl Jackson. Carl’s daddy was a musician, too, and he spent lots of hours working with me on the mandolin. Carl had gone on the road with several musicians, and the next year, he joined the Sullivan Family, a popular bluegrass gospel group. When the Sullivan Family was slated to play at a church near my home, I persuaded Enoch Sullivan, the patriarch, to let me play on a couple of songs. Oh, it was wonderful!

I was totally hooked. I begged and pleaded with Carl until he asked Enoch if I could go on the road with them that summer, and Enoch agreed. I felt my life had begun.

We played mostly Pentecostal churches on the back roads of the Deep South. People loved the Sullivan Family and welcomed us everywhere we went. When we played a festival at Lavonia, Georgia, I ran into Roland White. Roland played with Lester Flatt, and I’d met him the year before at Bean Blossom. We hung out some—at a bluegrass festival, hanging out means sitting around playing music.

Can you imagine the ecstasy of a twelve-year-old boy jamming with Roland White? What could make it more perfect?

I’ll tell you what—when the festival was over, Roland gave me his phone number and said if I could get permission from my parents to go on the road with them one weekend, to give him a call.

After a summer with the Sullivan Family, I knew that “the road” is a powerful thing. It has a way of changing and claiming you. Some people just aren’t cut out for it, but I loved it from the beginning. Mostly, to me, the road meant freedom. That’s what I had to give up when it was time to go back to school.

Not surprisingly, after spending the summer in my dream world I was a poor excuse for a student. The final straw came one day when a teacher came up behind me when I was supposed to be reading history and I had a Country Music Round up inside my history book. She busted me.

“Marty,” she said, “You could make something out of yourself if you’d get your mind off music and get it on history.”

“Ma’am,” I replied, “I’m more into making history than learning about it.”

On the strength of that remark—and something about my attitude and haircut—I was excused from school.

My poor parents. I’m sure they expected me to be sad and sorry about my situation. Instead, of course, I was formulating a plan. I suddenly had a few unexpected days free.

As soon as I got home, I called Roland to see if his invitation was still open. He got an okay from Lester. Before my parents even had a chance to discuss “my situation” with me, I met them crying, begging and pleading to join Roland White for the weekend. My parents knew full well who Lester Flatt was. They also knew that this was an extraordinary opportunity. So instead of spending the weekend grounded, as I’m sure my teacher intended, I was on a bus to Nashville!

The old bus station in Nashville was across the street from the Ryman Auditorium. When I got off the bus, I paused, purposely th

inking of where I’d come from. Then I took a look at the Opry to see where I wanted to go.

Within a couple of hours, I was on that bus I’d dreamed about, heading off with the guys toward Delaware for the weekend. As we traveled, Roland and I got out the mandolin and guitar and started playing some tunes. Lester came back to go to bed and stopped for a minute to listen. I guess he liked what he heard, ’cause he laughed and said, “Why don’t you do a couple of songs on the show tomorrow?”

That pretty much made my year.

Lester let me play all four shows the band did over the next two days. He was generous and gracious, building me up and giving me recognition during the shows.

When the weekend was over, I figured my life was downhill from there. How on earth would I ever pay attention to history when I’d played with Lester Flatt? I’d reached my dream; I’d grabbed the brass ring. Everything else would certainly seem drab and gray in comparison.

On Sunday, when the band was packing, I thanked Lester for letting me play with them. As I did, I could see the wheels turning in his head: old act, new blood, this might work. Also, in the space of a couple of days we had a routine of gags between us. The chemistry was there, and we had the beginnings of a friendship.

Lester suggested that if we could work out something about school, he would talk to my parents about joining him full-time.

I used most of the pay phones between Delaware and Tennessee begging my parents for a little more time. I had a lot to tell them—Lester had invited me to play the Friday night Opry, Roland had a hat I could use, I had money left over, and, oh, yes—Lester had offered me a job.

“A job? Marty, you’re in junior high school! You’re thirteen years old!”

“Don’t say yes or no now, Dad, please! One week—just give me one more week. Let me play the Opry.”

Tuesday at WSM radio was just business for Lester and the guys after so many years. But just last week, I’d been listening to this show at home, dreaming, just dreaming. And now . . .

Announcer Grant Turner read his Martha White script and added, “along with special guests Mac Wiseman and Marty Stuart.”

Dear God, I hoped my history teacher listened to that show!

I remember thinking and praying a lot that week. I was definitely happy, kind of lonesome and kind of amazed at how fast everything had happened. I not only prayed for guidance for myself, I prayed for my mom and dad—especially Mom. I asked God to comfort her and let her know I was all right.

And I thought realistically about my future. There was no family business to go into. I didn’t think I had a future as a cotton farmer, and I couldn’t see myself at a factory; two occupations chosen by many kids in my school.

So what did I want out of life?

I wanted to go places, see things, meet all sorts of people.

Most of all, I wanted to live in the world of country music. That Friday night, one week after I’d gotten off the bus and set my sights on the Opry, I was playing there. Roy Acuff, Tex Ritter, Brother Oswald . . . the number of greats performing that night went on and on. And then there was . . . Marty Stuart.

Yes, this was my world. This was where I wanted to be.

But was the timing wrong? Would I lose it all because I’d made it across the street in one week instead of in ten years?

I know that letting your thirteen-year-old go out into the world must have been a heavy decision. And, to tell you the truth, I don’t think my folks would have let me do it with anyone but Lester.

Lester arranged to meet with my folks in person. He assured them that I’d be well looked after, that I’d keep a little spending money and send the rest of my earnings to the bank. He was already talking to Lance Leroy, our manager, (our manager!) about the details of how to finish my education.

To this day, I’m sure that the thing that made the difference was that Lester Flatt promised to personally assume responsibility for me. Even in that short of a time, my parents could see that Lester was a man of integrity, a man of his word.

My parents agreed to give it a try. I told my mom and dad and sister good-bye and climbed onto the bus. As their cars faded from sight in the Alabama dust, I had to fight back tears. But I knew that beyond that cloud of dust there was a big world waiting, and I wanted to see it— every bit.

Marty Stuart

Copyright ©1992 Country Music Magazine. Used by permission.

A Little More Out of Life

Always be “work in progress.”

Tim DuBois

I wanted the job more than anything in my life. I was a veteran, a grown man, ready to marry and settle down, but I couldn’t keep a job and I was discouraged, all because I stuttered.

I had worked as a strawberry picker, a house painter, and even a fireman for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. I lost that job because by the time I was able to call out the train signals ahead we were already four or five miles down the track.

Then I heard that a candy company in Plant City, Florida, was looking for a route driver. And I’d heard that the owner of the company, a man named Miller, was a former stutterer who had somehow learned to control his stutter. A fellow sufferer, I was sure, would certainly understand and hire me. I set my heart on getting that job.

I got an appointment with Mr. Miller. When his secretary ushered me into his office, Mr. Miller, a kindly looking man who wore wire-rimmed glasses, looked me over. Then he asked why I wanted the job.

I couldn’t think of anything smart to say; I just started blurting the simple truth. “B-b-because I need the m-m-money,” I sputtered. I knew I sounded terrible, but I thought, We ll, at least he ’s hearing me at my worst.

For a long time, Mr. Miller didn’t say anything. Then finally he looked me straight in the eye. “Mr. Tillis,” he said softly, “I’m not going to give you a job.”

I stared at him, dumbfounded. He must have seen the surprise in my face.

“Oh, don’t get me wrong,” he said. “I think you’d do well. It’s just that I don’t have an opening right now.” Then he reached into his desk drawer and pulled out a piece of paper, worn and tattered. “I’d like you to take this home and read it,” he said. “Read it every night for a month.”

Hardly hearing his words, I reached out numbly, took the paper and stuck it in my pocket. Tears of disappointment burned my eyes. I turned my head away, told him good-bye and slumped out of the Miller Candy Company.

That night I felt totally dejected. Who wants a stutterer around? I asked myself in defeat. Nobody. And as long as I stuttered I would be a nobody. I had lived with this pain all my life.

I didn’t know that I talked differently until I started school. When I tried to talk everybody laughed. I began to withdraw more and more into myself.

My mother often said that God would help me solve my problem. I couldn’t see how. We were Baptists, but once a week Mama would take me up the road to a little Pentecostal church. I loved to listen to the singing in there, the guitars and the fiddles they used in those midweek services. And when I joined in the singing, I noticed that I didn’t stutter at all.

Mama would hold family songfests on the front porch every evening, all of us sitting around and singing for hours; I didn’t stutter a word. We found out that when a stutterer speaks, air gets trapped in his throat. But when he sings, for some reason the breathing apparatus works normally and there is no stutter. I sometimes wondered if I might go through life singing, never having to talk again.

But after the interview with Mr. Miller, I was prepared never to utter another sound. I took the piece of paper he had given me out of my pocket, ready to tear it to shreds. But something made me look at it. It was a prayer—a very well-known one, but one I didn’t know at the time: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

I read the words again. Then again. They were like the light at the end of a tunnel.

Accept the th

ings I cannot change. I could work at easing my stuttering, I knew, but I probably could never really change the way I talked.

Courage to change the things I can. What I could do something about were all my fears—fear of stepping out of my shell, fear of trying to be somebody, fear of thinking bigger than I had been doing.

God, grant me these renity. Here, I knew, was the key to the whole prayer. When, I wondered, was the last time I actually had reached out to God? Years earlier, when I was a kid, I had prayed that I would wake up one morning and talk differently. When it didn’t happen, I forgot about God. But from what I was feeling now, I was pretty sure that the Lord hadn’t forgotten about me.

Soon I was asleep—a deep and restful sleep. But though serenity came that night, it didn’t hang around all the time. And change didn’t come overnight either. I kept reciting that prayer, reminding myself of its words and their meaning, till I finally could place myself in God’s hands, in trust, without fear of what might happen to me.

I gradually grew aware of a desire deep within me to write songs, the kind of country music songs we had sung in the Pentecostal church. I learned to play the guitar and started writing. At the same time, I often thought of how enjoyable it would be to stand up in front of people and entertain them, but I knew this was a daydream because of my stutter.

Some months later, armed with some of my songs, I went to Nashville in hopes of getting somebody to listen to my work. One door led to another, and one day I got an appointment to audition for Minnie Pearl, one of the biggest names and greatest people in country music.

I was scared. As I went to the studio, I kept praying: “Your serenity, Lord. Your serenity.”

The audition went well and Minnie Pearl hired me as a backup musician and a songwriter. I was happy, but I stayed in the background for years and years, nowhere near my daydream of standing up and doing the entertaining myself, still frightened of what people would think of my Porky Pig stammer.

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Chicken Soup for the Soul of America

Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul

Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul

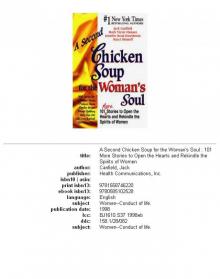

Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues

Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul

Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Chicken Soup for the College Soul

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul

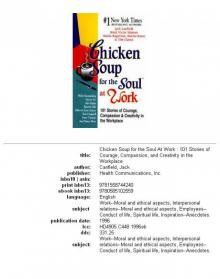

Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference

Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter

Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories

Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul Chicken Soup for the African American Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Soul 101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13

101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13 Christmas Magic

Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs Chicken Soup for the Country Soul

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul)

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul) A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul The Book of Christmas Virtues

The Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Little Souls

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II