- Home

- Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Page 12

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Read online

Page 12

My hair has become my own personal study on culture, on human nature and sisterhood. On a regular basis, I have people of all races stop me and comment on my hair.

It’s funny sometimes. I never anticipated this. White people don’t know what to think—nor do they seem to care all that much. Black people have a more complex reaction. Many are pretty cool about it, even if they would never go “that far” with their own heads. Some are downright hostile. I think it makes them self-conscious or something, but that is their issue, not mine. Many people sport dreads these days, but obviously not so many that they have completely emerged from an enigmatic status.

Recently, I was walking into the grocery store and a sharp sista stopped and said, “GURRRRLLLLLLLLL! I just LOVE your hair! Now, that is truly beautiful!”

She was with her man, who was also sharp, and he smiled in agreement.

I said, “Why thank you, Sista! I LOVE your hair, too!”

Now as I look back upon the journey my hair has taken, it seems Daddy knew something about the beauty of African American women’s hair that perhaps even we women didn’t know—we are naturally beautiful, and we all already have good hair .We have the hair that the Creator chose to crown us with. That’s good enough for me.

Lisa Bartley-Lacey

Gluttony to Glory

If you want to do better today than you did yesterday, you simply must believe you deserve it.

Iyanla Vanzant

Growing up in the heart of the Midwest, I was always labeled the “fat kid”—the kid with fewer friends, the biggest clothes and always the last to get picked on a team during recess. In every child-oriented social surrounding, whether it was drill team or Brownie troops, I stood out. This had nothing to do with my being black, but everything to do with my corpulent dimension. Things were so out of hand that my family bestowed on me the derogatory nickname “pig” as a way to describe me and my excessive eating habits.

I was raised by my great-grandmother, who would break my sleep on Saturday mornings with the smells of crispy Southern fried chicken, fluffy homemade buttermilk biscuits, dark country gravy and butter-colored rice. This was just breakfast—imagine what dinner was like! You see, Grandma was what you call ol’ school; she was not one for a bunch of mushy words, so cooking was one of her many ways of telling me she loved me. I adored this particular type of love, to the point where I allowed it to sculpt my life (and my figure), as if it were my god.

Grandma passed away by the time I reached high school. During my senior year I was weighing way over two hundred pounds and wearing a size twenty-four. I didn’t give my size much thought during my last year of high school. I really thought things had turned around for me when the “Denzel Washington” of Central High asked me to the prom. I felt as if I had grown wings and was about to sit beside God on the throne. Unbeknownst to me, I had graduated from the fat kid to the “fat chick.”

These are the words he heard when he told our peers he was taking me to prom. As I sat at home waiting for him to pick me up, all dolled up and looking as fine as I possibly could look, I watched the clock and waited and waited.

With each passing moment my heart cracked a little more.

He stood me up, and my emotions were now aflame. It was then that I discovered how much food would ease my pain. With each bite I became numb. Every time I’d chew I’d feel comfort and relief. Food quickly became my best friend, my lover and a way to ease the pain. With each painful experience came a reason to binge. The need to binge would take over if I didn’t get a promotion, if someone hurt my feelings, if I had a bad day at work, school, salon—it didn’t matter. I would binge at such a high rate, my body would give it back, and I’d see my comfort go down the toilet. Food was something I was sure would never hurt me, so I thought. At the age of thirty I was weighing over three hundred pounds and rocking a size twenty-eight dress.

It was at that point that my best friend, Zelema, who is thirty years older than I, gave me the weight talk. She informed me that there had to be deeper issues that were causing me to eat. In the beginning I didn’t want to hear it, because after high school I was sent to what people call a “fat farm,” with head shrinks and nurses roaming the floors. In other words, the Eating Disorder Unit at a local hospital. It hadn’t worked then, and I didn’t want to hear it now. But this was different. The words of wisdom and support were coming from someone who loved me and whom I loved. I pressured myself to stop and listen because she had been my umbrella during many storms and wouldn’t lie to me. Zelema is president of a college and has that take-charge attitude, anyway, but she got me when she said, “I’ll stick by you every ounce of the way.” I knew it wasn’t going to be easy because I have the common, black woman’s figure—the big hips, legs, breasts and butt . . . all there. All willing to stay!

Over the course of six years I’ve lost over one hundred pounds and gone down to a size fourteen. I got smaller by eating right, exercising and getting rid of the emotional pain. Though I had lost weight and was looking great, this didn’t stop prom night from happening again eighteen years later. I was dumped again by another pretty boy who thought I was too fat, but he added a new twist; he called me ugly as well. Granted, I’m no supermodel, neither am I Medusa. I could feel my heart beating the power of a thousand African drums and my temperature rising to that same number. My big brown eyes were filled with water, and my light brown skin was the color of a beet. Zelema begged me not to resort to food as comfort, but eventually I did. Then the spirits of Mary and Martha came over me, and the weeping ended. I hit the gym harder and cut out even more fattening foods from my diet. I lost another twenty pounds. This enabled me to wear more appealing clothes; my cheekbones became Pikes Peak; my cocoa brown skin became flawless, without a blemish. Five months later, I ran into my second “prom date” in the ritzy part of town. The sight of me brought a hungry gleam to his eyes, and two rows of small pearls appeared across his freckled face. He wants me back; I can see and feel it. However, I won’t be having that!

I lost the weight and gained a lot of self-dignity in its place! It was then I realized I had fallen in love with myself. Food was no longer my only option to deal with negative situations. I do not cry, nor run to Zelema for cover. I have finally grown into my own.

Lindale Banks

Getting Real

The day I looked at myself with a natural was the first time I liked what I saw.

Marita Golden

I was delighted and relieved when the Afro first became popular. For me, it meant instant deliverance from the tyranny of the straightening comb that had not only pressed my unwieldy hair for years, but pressed me, as well, into believing that I had little recourse except to burn myself often to be beautiful. Finally, I could relax and be my natural black self.

Mother, however, did not share my elation at this new development. In fact, when she came home one day and caught first sight of my woolly head, she dropped both of her grocery bags, and it was not immediately clear if the wail she emitted originated in her throat or from somewhere deep in the recesses of her soul. Even after I had wiped up the last remnants of broken eggs and spilt chocolate milk from the floor, Mother was still fuming well into the night.

At first I assumed that her initial overreaction would be just a temporary thing, but as time went on, it became increasingly clear that adapting to the new “bush” hairdo was not an item on Mom’s to-do list. And when I parted my coarse hair down the middle the next day and wore an Afro puff on each side of my head, it just about pushed Mother over the edge. In fact, she refused to speak to me for several days, and when she did, it was with such an enduring sadness, one might have thought that there had been a death in the house.

“White folks,” she murmured one morning, finally emerging from her long silence, “never even knew y’all hair was that bad,” as if its true texture was some awful secret that people without color had to be kept safe from. “It’s an abomination, and I, Rena Davis Mitchell, will never sto

op to wearing my hair like ‘that’!” she announced before retreating to her room.

Mother simply couldn’t fathom that I had grown tired of living in constant anxiety of drizzly August days, of sudden spring showers. Tired of frying hair late into the night only to sweat it right back to where it started in our un-air-conditioned house, my hair on loan as it were, like Cinderella’s pumpkin at midnight. Tired of living out of sync with a universe that had already designed us without flaw, except that no black voice had ever affirmed that to me. Tired of the weekly scalp fry that transformed me into what I was not and could never be, or more specifically, what I could be for a few days or so—provided the humidity didn’t rise or, God forbid, the rickety window fan didn’t sputter and tap out.

The judging starts very early on when black mothers, grandmas and aunties gather crib-side to gauge the tenuous texture of their newborn’s hair on some obscure scale, where kudos are reserved only for the softer-haired ones—hushed silences for all others. It is here that first fears are sealed. To deny the truth about oneself, I thought, was to deny one’s own heritage, one’s very DNA, the true essence of one’s being.

Still, on some level, I couldn’t fully blame Mother for her archaic beliefs. After all, in her day, she had few, if any, positive black role models to emulate. She, like most of the black women I knew, lived most of her adult life in hiding.

“We, as women,” she often insisted, “must suffer to be beautiful.” In her mind, that meant burning the hair to the quick and limiting access to anyone who might see it in its natural state. When I looked around, I observed that many of the women in our family perpetuated the same myth by hiding their hair beneath turbans or wigs.

Then it happened. I came home one day to discover that Mom had done the unthinkable—shaved her head totally bald. When I saw her, I immediately backpedaled, out of the front door, fearful that I had finally pushed my poor mother to the brink. She calmly explained that her childhood friend Eunice had lost most of her hair to cancer treatments. Mother apparently had decided she wanted to be there for Miss Eunice in a big way, so in a drastic move, shaved off her own hair. It was no small feat for a black woman to sport a shaved head in the ’60s, least of all for my mother.

Amazingly, through it all, something wonderful began to emerge. By helping her friend, mother was forced to wrestle with her beliefs about her own beauty. I spied her on occasion observing herself in the mirror, slowly coming to terms with the budding, coarse strands she saw there. I took full advantage of this precious time to encourage her.

I helped condition and nurture her and Miss Eunice’s hair.

This was a special time for them and for me. I eavesdropped on their adult chatter, drank from their wisdom, admired the way their heads nodded in loving accord. I was awed by the beauty of Mom’s selfless act, but also realized that it was a turning point for her. A confidence

I’d never seen before emerged in her. Even after we lost Miss Eunice, Mother still sported a lovely crop of natural hair, sometimes trimming it down to a regal skullcap. My mother, the eternal poster child for “bone-straight” hair, had become a trendsetter in her own right, instilling confidence among her family and peers, many of whom emulated her and retired their much-used straightening combs as well.

It is a muggy August morning. At daybreak, the same dew that clings to the pebbles scattered at our feet clings to us as well, to our bodies, to our natural hair. My mother and I stride along the silver stretch of beach for our morning walk—a daily ritual. Years ago each of us might have spent these precious moments in quiet desperation rifling through our bags for a plastic rain hat to shield us from the truth we knew would come. Today no such thoughts intrude on our communion with each other. Today we affirm our Creator’s knowing hand in his creation. Today we hold our heads high with nothing hampering us, and stride boldly, in our magnificence, into dew-dropping day.

Elaine K. Green

Crown of Splendor

When I look at my mother and her sister-friends Exchanging their wisdom, Treasuring their memories,

Laughing so hard,

They end up shedding tears

Entrusting their secrets

Sharing their fears

Becoming wiser more than older

Experiencing new things,

Becoming bolder.

I adore

Their splendor.

This too, is what Solomon must have done,

For he writes in Proverbs

16:31 “Gray hair is a crown of splendor;

It is attained by a righteous life.”

As I look at the silver that surrounds my mother’s face,

She proudly wears her crown of splendor,

She says, “It’s not just gray, it’s grace.”

It’s proof that I’ve lived and am still living,

Making the most of the life I’ve been given.

That’s why we encourage daughters when

Their faith is shaken.

We know the rewards of the road

Less taken.

We want our daughters to attain their own crown of

splendor.

We dedicate our lives to be your teacher and defender.

Attaining this crown doesn’t come by chance or a whim.

It’s a result of a life dedicated to him.

That’s why we’re examples not in word,

But in deed.

You represent fertile soil into which

We plant our wisdom seed.

Look at your image in the mirror,

And I hope you see me.”

As I look at my reflection,

I see my crown of splendor is slowly heading my direction.

As I stroke my few strands of gray,

Or rather grace,

I see my mother and her sister-friend’s face,

Exchanging their wisdom,

Treasuring their memories,

Laughing so hard,

They end up shedding tears,

Entrusting their secrets,

Sharing their fears.

Becoming wiser more than older,

Experiencing new things,

Becoming bolder.

They adore

Their splendor.

I adore

Their splendor.

Royalty surrounds me.

Sheila P. Spencer

Birth of a Nappy Hair Affair

We teach you to love the hair God gave you.

Malcolm X

More than eight years ago, I had my first affair for women with nappy hair. It was intended to be a simple hair-grooming session, an opportunity for me and my girlfriends to get together on a Sunday afternoon and do our own hair.

There were some who thought I was trying to revive an African tradition, but as much as I embrace some traditions of the motherland, what I had in mind when I decided to have a gathering wasn’t that deep. All I wanted to do was offer a place for my friends who wear African-inspired and natural hairstyles to be among kindred spirits and come get their hair done for free.

At my house their unapologetically nappy heads would not stand out in the crowd. On that one afternoon they could be assured they would have majority status. At my house their royal crowns would be the rule, not the exception.

I also had selfish reasons for sponsoring the gathering. I wanted to take a trip back to my childhood. I missed the moments of bonding when the females in our house got together to do hair.

I am not talking about the traumatic Saturday night rituals when my mother fried our hair in preparation for church on Sunday morning. That’s when the sight of her brandishing the hot comb, the hissing sound it made when it came into contact with my grease-laden hair and the peculiar smell of something burning on my head made me wish I was born bald.

What I missed were the more natural moments, when my mother placed her healing hands directly on my head.

I remembered how comforting it was nestling between her strong knees as

she oiled and massaged my scalp with her fingers before brushing, combing and arranging my hair into a simple style of plaits or ponytails.

I would lean back, close my eyes and surrender to her firm but gentle touch.

Being the eldest daughter, I often did my younger sisters’ hair, and when my mother was too tired to do her own, we would do it for her. Those were the times when we were closest. Having the hair affair would give me an opportunity to recreate such moments at my home with my extended family of sister-friends.

I got the idea one day at the office after listening to my friend and co-worker lament about how hard it was to find the right hairstylist to do her locks. As a temporary solution I suggested that she come to my house so we could do each other’s hair. I told her I knew other women with similar concerns, so we could make it a communal affair.

I decided to have it on the third Sunday in May. It was an experiment. I didn’t really know what to expect. I never imagined that eight years later I would still be having what has now come to be known as Hair Day.

Hair Day has evolved into much more than grooming sessions. At these gatherings my sister-friends and I form a circle of solidarity and support. We celebrate our hair through storytelling and poetry readings and endless testimonials about our journey to appreciate ourselves as we really are.Hair Day is a time when my friends come to relax. They come to talk and sometimes vent about those who have judged themharshly for their choice to be themselves.

Our circle is an eclectic mix of Ivy League pedigrees and sisters with no degrees. We have mothers and daughters, women who work and women in transition. We have artists, writers, teachers and students, African dancers and sisters who drum.

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul: Second Dose Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Ocean Lover's Soul A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Breast Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Bride's Soul A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

A Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Chicken Soup for the Soul of America

Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul on Tough Stuff A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

A Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul

Chicken Soup for Every Mom's Soul Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dog Lover's Soul A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

A Second Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues

Chicken Soup for the Soul the Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls: 3 Colorful Stories to Warm the Hearts of Children Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul

Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers

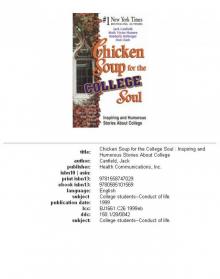

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Chicken Soup for the College Soul

Chicken Soup for the College Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters

Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Dieter's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work 101 Stories of Courage Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Beach Lover's Soul Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference

Stories About Facing Challenges, Realizing Dreams and Making a Difference Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul II Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Girl's Soul Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter

Chicken Soup for the Kid's Soul: 101 Stories of Courage, Hope and Laughter Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Cancer Survivor's Soul Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Military Wife's Soul A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 4th Course of Chicken Soup for the Soul Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories

Chicken Soup for the Soul: All Your Favorite Original Stories Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul

Chicken Soup for the Expectant Mother's Soul Chicken Soup for the African American Soul

Chicken Soup for the African American Soul 101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13

101 Stories of Changes, Choices and Growing Up for Kids Ages 9-13 Christmas Magic

Christmas Magic Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music: The Inspirational Stories behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs Chicken Soup for the Country Soul

Chicken Soup for the Country Soul Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul)

Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul Daily Inspirations (Chicken Soup for the Soul) A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul

A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul The Book of Christmas Virtues

The Book of Christmas Virtues Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work

Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Little Souls

Chicken Soup for the Little Souls Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition

Chicken Soup for the Soul: Reader's Choice 20th Anniversary Edition Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas

Chicken Soup for the Soul Christmas Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III

Taste of Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul III Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul

Chicken Soup for the Unsinkable Soul Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II

Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul II